-

Recent Posts

Recent Comments

- Kate C on MORE HOT-WEATHER MURDER

- Kate C on SWEET DANGER by Margery Allingham

- Kate C on A MAN LAY DEAD

- Kate C on CHRISTIANNA BRAND

- Kate C on CLOWN TOWN

Archives

- February 2026

- January 2026

- December 2025

- November 2025

- October 2025

- September 2025

- August 2025

- July 2025

- June 2025

- May 2025

- April 2025

- March 2025

- February 2025

- January 2025

- December 2024

- November 2024

- October 2024

- September 2024

- August 2024

- July 2024

- June 2024

- May 2024

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- October 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- May 2012

- March 2012

- January 2012

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

Categories

Meta

STANDING AT THE EDGE

In late summer twenty seven years ago, I stood at a tram stop. With fifteen minutes or so to wait, I decided to pop into the nearby bookstore. It specialised in New Age and spiritual and religious books; I wasn’t particularly interested so why I picked up this particular book, I have no idea. But as I began to read I experienced an uncanny sense of recognition. This makes sense. I may well have missed the next tram. I still have that book.

In late summer twenty seven years ago, I stood at a tram stop. With fifteen minutes or so to wait, I decided to pop into the nearby bookstore. It specialised in New Age and spiritual and religious books; I wasn’t particularly interested so why I picked up this particular book, I have no idea. But as I began to read I experienced an uncanny sense of recognition. This makes sense. I may well have missed the next tram. I still have that book.

It’s Seeking the Heart of Wisdom by Joseph Goldstein and Jack Kornfield,and an introduction to the practice of vipassana or insight meditation. I bought it either ‘at the right time’ or ‘just in time’, depending on how you look at it. I wasn’t doing well in early 1993, and exploring Buddhist philosophy and practicing meditation helped steady me. Back in 1993, it was all totally new to me; over the years that I’ve acquired a small shelf of books on Buddhist philosophy and meditation. I don’t meditate regularly, but there are aspects of Buddhist philosophy that support me daily. I still read Seeking the Heart of Wisdom every few years, and I have other titles by both authors; the funny, wise, Jewish-grandmother Sylvia Boorstein is a favourite, as is Pema Chodron. And here is a new book and a new writer. Timely, or perhaps (again) ‘just in time’.

Joan Halifax – Zen priest, Buddhist teacher, anthropologist, writer – examines what she calls ‘edge states’.

Joan Halifax – Zen priest, Buddhist teacher, anthropologist, writer – examines what she calls ‘edge states’.

Over the years, I slowly became aware of five internal and interpersonal qualities that are keys to a compassionate and courageous life, and without which we cannot serve, nor can we survive. Yet if these precious resources deteriorate, they can manifest as dangerous landscapes that cause harm.

The five states that Joan Halifax identifies in this book are altruism, empathy, integrity, respect and engagement. I’m sure nearly everyone would nod and agree – “All good!”

But Halifax writes that manifesting these qualities can be like walking along the high ridge of a mountain. The view is sublime, but if a person loses their balance and slips over the edge, any one of these qualities, these ‘assets of a mind and heart’, can become harmful and cause suffering.

An example is altruism. Unselfish service, selfless acts, self-sacrifice… these are admirable, inspiring and in fact necessary if communities and families are to flourish. Just think of mothers! And volunteers of all descriptions and kindly neighbours and good Samaritans and those heroic people who jump in to dangerous situations to save lives. However, Halifax explores the darker side, ‘help that harms’ or pathological altruism.

There are a few varieties. In one, people ignore their own needs. They may end up feeling resentful, overburdened, guilty and frustrated – and thus not in great shape to keep altruism positive.

In another, altruism is rooted in a need for approval, a desire to ‘fix’ people, hubris, even an urge to power over others. Halifax gives the example of international aid gone wrong, where Westerners think they can change the world but don’t actually take the time and effort to find out what people need and want.

There’s lots in this book for me to think about. And also to do. Roshi Joan speaks from her own experience – working in prisons, hospitals and clinics, with dying people and their families, in the civil rights movement – and provides guidance and practices to help foster calm and compassion in difficult circumstances. As I move into the aged care sector, I will likely need this book.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

PHOSPHORESCENCE

There are few things as startling as encountering an unearthly glow in the wild. Glow-worms. Ghost mushrooms. Fireflies. Flashlight fish. Lantern sharks. Vampire squid. Our forest floors and ceilings, our ocean depths and fringes are full of luminous things, creatures lit from the inside. And they have, for many centuries, enchanted us, like glowing missionaries of wonder, emissaries of awe.

There are few things as startling as encountering an unearthly glow in the wild. Glow-worms. Ghost mushrooms. Fireflies. Flashlight fish. Lantern sharks. Vampire squid. Our forest floors and ceilings, our ocean depths and fringes are full of luminous things, creatures lit from the inside. And they have, for many centuries, enchanted us, like glowing missionaries of wonder, emissaries of awe.

Is there anything more beautiful than living light?

Julia Baird could not have known, while she was writing Phosphorescence, just how timely her book would be. Subtitled ‘on awe, wonder and things that sustain you when the world goes dark’, it’s been a lovely counterbalance to the gusts of bad news that keep swirling around us.

It’s not really a memoir, nor is it self-help or a collection of essays or a book of nature writing – but contains elements of all four. Some of the impetus to write Phosphorescence is Baird’s experience of pain and illness. In 2015, she was diagnosed with a rare kind of cancer, which recurred twice, needing surgery and rounds of chemo. Though Baird talks about her cancer experience, it’s not a blow-by-blow account. As Lissa Christopher wrote in her ‘Lunch with…’ interview in the Melbourne Age (‘Spectrum’, 13/6/20) illness is ‘the dark background against which the rest glows’.

And glow it does. There are lyrical and lovely descriptions of swimming and walking and observing the natural world, along with excursions into the science of why such things are so very good for us. Who knew that forest bathing was a prescription? Baird urges us to pay attention; to embrace the soothing power of the ordinary; to seek nature; to experience awe whenever we can.

Awe makes us stop and stare. Being awestruck dwarfs us, humbles us, makes us aware that we are part of a universe unimaginably larger than ourselves…

Wonder is a similar sensation, and the two feelings are often entwined. Wonder makes us stop and ask questions about the world, while marvelling over something we have not seen before, whether spectacular or mundane.

Nearly thirty years ago, in mid-1991, I woke from a dream. We all have lots of dreams, and most of them vanish from our minds almost as soon as we wake, but this I’ve never forgotten. It was nothing Freudian or Jungian or fantastical, just a voice, saying something I still find deeply mysterious. It said, “In-dwelling light.”

Every now and then I think about that phrase. Where did it come from, what does it mean, was it a mantra, was it a message? Phosphorescence has me wondering and pondering all over again.

Phosphorescence Julia Baird Fourth Estate 2020 $32.99

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

JANUARY STARS

When their parents leave for New Zealand to sort out a family emergency, sisters Tash (aged 12) and Clancy (who’s 14) are sent to stay with their aunt. When when she goes away for the weekend, what could possibly go wrong?

When their parents leave for New Zealand to sort out a family emergency, sisters Tash (aged 12) and Clancy (who’s 14) are sent to stay with their aunt. When when she goes away for the weekend, what could possibly go wrong?

The girls impulsively bust their grandfather out of his aged care facility and go on the run, that’s all.

Pa has been living at The Elms since he had a stroke. He’s in a wheelchair, and he’s suffering from aphasia – which means he’s lost his words. But he’s still full of spirit, and a willing accomplice to his grand-daughters.

They want to find a better place for Pa. Anxious by nature, Clancy is at first hesitant, and tries to hold her older sister back. But they’re united by love for their grandfather and in the end, they’re simply carried along by the momentum of their adventures. The journey takes them from the empty family home in a leafy suburb, to a mysterious bookshop in a derelict inner-city arcade, to an ashram in the bush and a beach-house by the ocean. An elderly gent in a wheelchair doesn’t make for easy travelling, and the trio need all their resourcefulness and grit to manage. Which they do, with maybe a little extra help, as sensitive Clancy begins to suspect they’re being guided by the spirit of their dead grandmother.

This is a warm-hearted and heart-warming story. It encompasses many large and significant themes – such as the pull-and-push struggle between the family and the individual, the challenges of ageing and of caring for our elders – but these are wrapped up in the two girls’ endearingly shambolic quest. Over their time on the run, bold Tash and anxious Clancy develop a closer and more understanding bond as they come to see that though they have very different personalities, together they make a great team.

Road-trip novels are by their nature episodic, and I thoroughly enjoyed the cast of vivid and diverse characters – taxi drivers, shopkeepers, booksellers, public transport staff, messy apartment-dwellers, kind and helpful strangers – who pop in and out of the adventure.

When I was a bookseller, I noted that there seemed to be a gap in the market. Middle-school children who read above their age level, but who want gentle realistic family stories – not fantasy, horror or gross-out humour – weren’t well catered for. The January Stars is one book I’d have been delighted to recommend.

The January Stars Kate Constable Allen&Unwin RRP $16.95

Posted in Uncategorized

1 Comment

HARD-BOILED ANXIETY

It’s counter-intuitive, but there’s something so calming about old school detective fiction. It’s often been said that it’s all about the ‘moral universe’; these are stories with a certain outcome in which the good prevail and the bad are punished. I’m not sure it’s just that. I like the process, too, the problem solving, the working out of motive and opportunity, the separation of red herring from genuine clue and the patient untangling of knots and snarls until it all comes out in the end.

In the last couple of weeks I’ve continued my Wimsey crime spree on Kindle. It’s coincided with (and I hope it hasn’t caused) a bout of insomnia. So, midnight reading has been Whose Body?, The Nine Tailors, Clouds of Witness, Murder Must Advertise and Unnatural Death. But enough is enough, and especially enough of Lord Peter with his monocle and silly-ass pose – and the unquestioned hilarity of the lower and middle classes. Ow, t’ funny way they do talk!

I have a trial membership of Kindle Unlimited – around $15 a month, and any book you want from the dedicated list – so after exhausting Dorothy Sayers, I decided to cross the Atlantic and move up a couple of decades.

I have a trial membership of Kindle Unlimited – around $15 a month, and any book you want from the dedicated list – so after exhausting Dorothy Sayers, I decided to cross the Atlantic and move up a couple of decades.

I tried searching for an old favourite, Ross McDonald. There were none available on Kindle Unlimited, but what I did find was a fascinating book called Hard Boiled Anxiety by Karen Huston Karydes.

It’s Freudian literary criticism, zeroing in on three masters of the ‘hard-boiled’ genre – Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammet and Ross McDonald – and the twisted origins of their fiction. Behind the tough-guy private eyes are three seriously messed-up writers. Each of these men had complicated relationships with their parents and with women, so Karydes’ Freudian interpretations are an easy fit. And of course, what is the underworld but the subconscious? McDonald is a particularly apt subject, because he’d had extensive psychoanalysis and was perfectly aware that his clingy, demanding women and their sons or younger lovers referenced Oedipus. Even more revealing were the excerpts from McDonald’s confessional memoir. It seems that McDonald used his detective hero Lew Archer to heal himself.

This is lively, entertaining and illuminating lit crit. And what a great cover.

Posted in Uncategorized

2 Comments

WINTER BOOK

Every time I go to see my chiropractor, there’s a little ritual. After the half hour drive to Daylesford, a pot of tea. Of course. There are two Op Shops right across the road from the clinic. And afterwards, since I have to walk around for twenty minutes or so before getting in the car again, there are the shops. The bookstore in Vincent Street – Paradise Books, new and second-hand – is great for browsing. And there are oodles of places selling dreamware. Dreams, as in ‘my impossible perfectly curated life’. Silk scarves, French cookware, alpaca throws. Hand-crafted jewellery and chocolates and gin. Soap made by artisans in Sicily from virgin olive oil which look like large lumpy baseballs of snot…

Every time I go to see my chiropractor, there’s a little ritual. After the half hour drive to Daylesford, a pot of tea. Of course. There are two Op Shops right across the road from the clinic. And afterwards, since I have to walk around for twenty minutes or so before getting in the car again, there are the shops. The bookstore in Vincent Street – Paradise Books, new and second-hand – is great for browsing. And there are oodles of places selling dreamware. Dreams, as in ‘my impossible perfectly curated life’. Silk scarves, French cookware, alpaca throws. Hand-crafted jewellery and chocolates and gin. Soap made by artisans in Sicily from virgin olive oil which look like large lumpy baseballs of snot…

In one particularly beautiful shop, Frances Pilley (also in Vincent Street), I buy these spiral-bound notebooks with a beetle on the cover.

I’ve been keeping a journal (and I mean actually keeping it up for any length of time) this year and so far, I’ve filled two of these notebooks. I have three more, which should last me to the end of 2020. I’ll be onto my next one by the end of the week. and I suppose if I’ve had a summer book and a coronavirus book, this next one will be my winter book. Right on cue, the season has changed. I am looking out of the window right now, and rain is falling and the last bright leaves are shaking on the wind-tossed quince tree. A poor, wet grey shrike-thrush is sitting on a bare branch right only three or four metres away through the glass. Oh! He must have felt my gaze, because now he shook himself and flew away.

I’ve been keeping a journal (and I mean actually keeping it up for any length of time) this year and so far, I’ve filled two of these notebooks. I have three more, which should last me to the end of 2020. I’ll be onto my next one by the end of the week. and I suppose if I’ve had a summer book and a coronavirus book, this next one will be my winter book. Right on cue, the season has changed. I am looking out of the window right now, and rain is falling and the last bright leaves are shaking on the wind-tossed quince tree. A poor, wet grey shrike-thrush is sitting on a bare branch right only three or four metres away through the glass. Oh! He must have felt my gaze, because now he shook himself and flew away.

Apart from the mundane and daily and ephemeral, the Summer Book is about heat and smoke and fires. Some anger, but mostly grief, that in this country we can’t seem to get past politics and just do what’s needed to cut our emissions. And Coronavirus Book contains a fair bit of uncertainty and fear and obsessive checking on the figures, as well as sorrow and sadness and a selfish nostalgia my old life, including those lovely and indulgent trips to Daylesford which seem like something from a fairy tale past.

The notebook also contains what I could call my Covid-19 Epiphany.

After 24 years as a bookseller, I decided that I need a change. So I have finished up – goodbye Bookroom! – and I’m hoping to start a Cert III in Aged Care in mid-July. As well, at almost the same time, I’ll be sending the first draft of my new novel to the wonderful freelance editor Janet Blagg. She worked with me on “How Bright” and she’s very kind, but it’s always a racking process. Is this book rubbish? Does it make sense? Did it achieve any of what I wanted it to achieve?

Maybe Winter Book should actually be Scary Book. Or “Are You Mad?” Book.

Or just New Book.

Posted in Uncategorized

2 Comments

VIEW FROM THE CHEAP SEATS

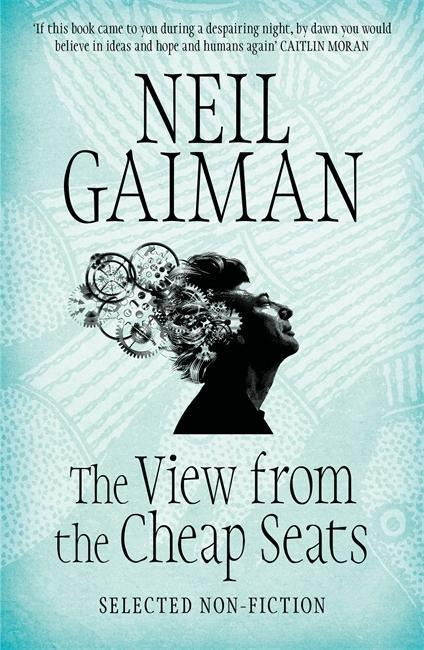

“We who make stories know that we tell lies for a living. But they are good lies that tell true things, and we owe it to our readers to build them as best we can. Because somewhere out there is someone who needs that story. Someone who will grow up with a different landscape, who without that story will be a different person. And who with that story may have hope, or wisdom, or kindness, or comfort.

“We who make stories know that we tell lies for a living. But they are good lies that tell true things, and we owe it to our readers to build them as best we can. Because somewhere out there is someone who needs that story. Someone who will grow up with a different landscape, who without that story will be a different person. And who with that story may have hope, or wisdom, or kindness, or comfort.

And that is why we write.”

From Neil Gaiman’s acceptance speech for the 2009 Newbery Medal, which was awarded to The Graveyard Book.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

GAUDY NIGHT

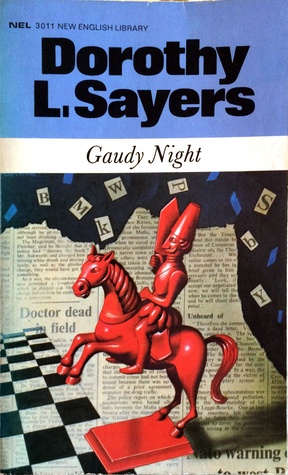

After finishing Square Haunting by Francesca Wade, I decided to look up some of Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries. I remembered Gaudy Night was one of my mother’s favourite detective novels so I decided to start there, near the end of the series and not at the beginning.

After finishing Square Haunting by Francesca Wade, I decided to look up some of Dorothy Sayers’ Lord Peter Wimsey mysteries. I remembered Gaudy Night was one of my mother’s favourite detective novels so I decided to start there, near the end of the series and not at the beginning.

It’s the mid-1930’s, and detective novelist Harriet Vane arrives in Oxford for a ‘gaudy’ (a college feast or reunion) at Shrewsbury, her old college. Scarred by the publicity and scandal of her murder trial (see Strong Poison), she’s reluctant to go…but once she’s there, she finds herself back under its familiar spell. Harriet rediscovers Oxford; the mellow old buildings, the river, the streets and shops. She also renews her love for the university, the institution; the traditions of scholarship and learning and ‘the life of the mind’. She wonders if she could insulate herself from the worries of the world, and become a scholar…

But (since this is a detective novel) she also finds herself in the middle of a mystery. Someone in this all-female community has been sending poison pen letters and committing minor acts of vandalism. Is it a member of the staff (‘scouts’), a student, an academic?

This book was written in the 1930s, when women’s demands to participate in higher education still met with resistance. Female academics and intellectuals were commonly caricatured as unlovable and unfeminine, if not downright bitter and twisted. (Well, why not be bitter? Oxford did not admit women to full academic status until 1921 and Cambridge – can you believe it? – not until 1947!). It soon becomes clear that Shrewsbury College’s female intellectuals are the targets of an anti-feminist who wants to cause a scandal in the academic community. With the attacks becoming nastier and more frequent, Harriet is asked to investigate. Eventually, she turns to Lord Peter Wimsey, her friend and unsuccessful suitor, for assistance. In its final pages, the mystery is tragically solved and Harriet and Peter find each other at last.

Back to my mother. As I’ve aged, I’ve come to see her in a different light (like, she was a person!). Yes, she was strong, stoic, intelligent, self-disciplined, brave – quite the feminist icon. She was also – if I read her rightly – a raging romantic. In my youthful self absorption, I’d missed that. Gaudy Night is both a mystery and an achingly romantic love story. It’s the book where Harriet (at last!) realises that Peter is her soul mate. And he, after years of fruitless courtship, gets his heart’s desire. The scene on the riverbank, where Harriet studies Peter’s face as he sleeps, had me reaching for my (metaphorical) fan. Hot! and yet with nothing explicitly sexual.

I can imagine that for my mother, as a fiercely intelligent young woman in the early 1940s, the fiercely intelligent Harriet might have been a heroine. Not bitter, not twisted. Successful, capable – and lovable, too.

Posted in Uncategorized

2 Comments

STILL SMILING

Last year, as part of the Castlemaine State Festival, large format posters of local artists, writers, performers and other creative types were plastered around the town. Despite rain, wind, sun and the work of random rippers and taggers, I am still there. Thank you to my lovely sister-in-law Lyndell for sending me this smile.

Last year, as part of the Castlemaine State Festival, large format posters of local artists, writers, performers and other creative types were plastered around the town. Despite rain, wind, sun and the work of random rippers and taggers, I am still there. Thank you to my lovely sister-in-law Lyndell for sending me this smile.

Posted in Uncategorized

Leave a comment

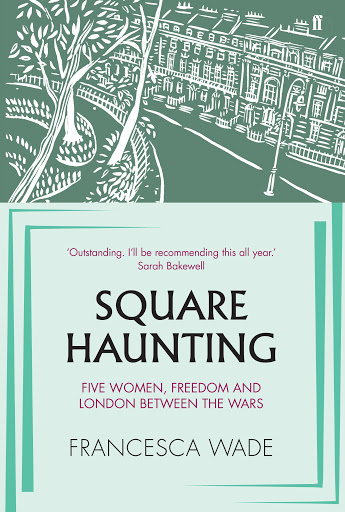

SQUARE HAUNTING

This group biography explores the lives of five extraordinary women who all lived in secluded Mecklenburgh Square, on the fringes of Bloomsbury, between the two world wars. The women are H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) a modernist poet: Dorothy Sayers, author of the Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels: Jane Ellen Harrison, classicist and translator: Eileen Power, historian, broadcaster and pacifist: and Virginia Woolf who needs no introduction. The unusual title actually comes from Woolf; in 1925 diary entry, she wrote of the pleasures of “street sauntering and square haunting”.

This group biography explores the lives of five extraordinary women who all lived in secluded Mecklenburgh Square, on the fringes of Bloomsbury, between the two world wars. The women are H.D. (Hilda Doolittle) a modernist poet: Dorothy Sayers, author of the Lord Peter Wimsey detective novels: Jane Ellen Harrison, classicist and translator: Eileen Power, historian, broadcaster and pacifist: and Virginia Woolf who needs no introduction. The unusual title actually comes from Woolf; in 1925 diary entry, she wrote of the pleasures of “street sauntering and square haunting”.

Each of these women claimed, to use Woolf’s words again, “a room of one’s own”, and a life of their own. It’s a fascinating and often moving study of five very different women who were united in their intelligence, curiosity and creativity. It makes me sad, nearly a century on, to read how convention and male authority constrained their ambitions; how difficult it was for them to reach their potential and achieve recognition.

At the end of the book Wade writes:

…the legacy of these women’s lives lives on…in future generations’ right to talk, walk and write freely, to live invigorating lives.

I’m sad too because I know that as women we still don’t always feel that we have the right to the lives we want.

Square Haunting by Francesca Wade Faber&Faber $39.95

Posted in Uncategorized

4 Comments