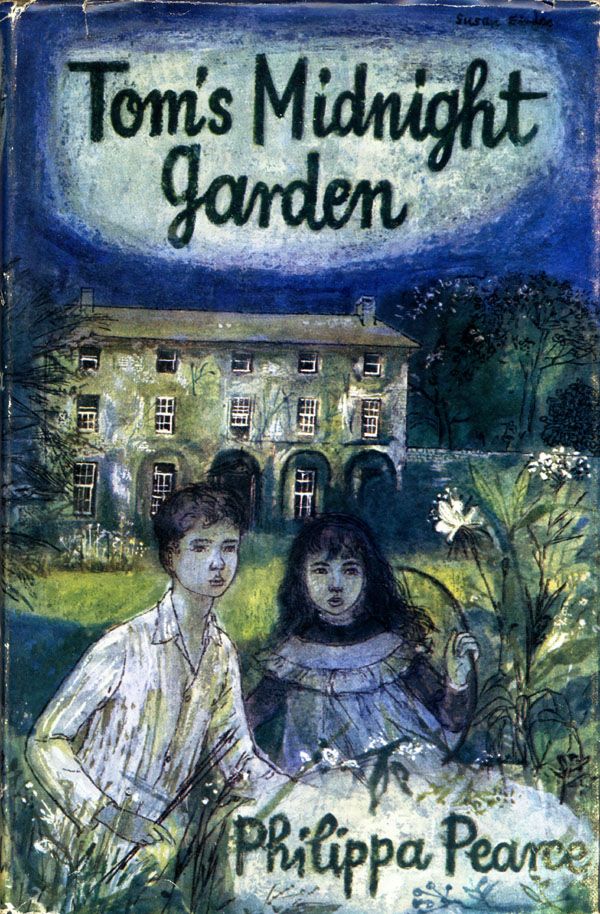

These past days have been so hot that I’ve been spending most of my time – when not actually at work – sitting close to the air conditioner and reading. In an attempt to cheer myself up and change the weather, at least internally, I re-read three of my favourite English children’s books, each of them magical and beloved and beautiful – The Midnight Folk, Tom’s Midnight Garden and The Children of Green Knowe. An exercise in nostalgia, yes – but how wonderful to be transported to the snowy winters and cool summers of English children’s literature when it’s 45 degrees outside and 35 in the front of the house.

My first encounter with Tom’s Midnight Garden was as a BBC radio serial. This is another cooling thought; the ABC played these children’s serials early on a Sunday morning and Dad used to bring the transistor radio in to me so that I could listen to it in bed. Then, as often as not, we’d go for a walk together on the beach which was just through our back gate. My memory paints a Port Phillip Bay that was always calm and flat, with sandbanks exposed, a few early boats out on the water, a few early walkers like us. When we got home, Dad made what he called ‘baconized egg’ (scrambled eggs with chopped, fried bacon bits) for the two of us; the rest of the family missed out, this treat was only for early risers.

Tom’s Midnight Garden is one of the celebrated treasures of children’s literature – still in print – there’s a gorgeous Folio Society edition – and I’ve just seen the new graphic novel. The writing is so beautiful and perfect and intelligent and sensitive – the ‘time-shift’ is so well handled – here, I’d better just quote!

Tom’s Midnight Garden is one of the celebrated treasures of children’s literature – still in print – there’s a gorgeous Folio Society edition – and I’ve just seen the new graphic novel. The writing is so beautiful and perfect and intelligent and sensitive – the ‘time-shift’ is so well handled – here, I’d better just quote!

This is the section where Tom has found himself in the hall of the old house where his aunt and uncle’s flat is. It’s mysteriously gone back in time, to a room filled with stuffed animals, umbrella stands, paintings, rugs, fishing rods, peacock feathers, chairs and other furniture.

…Tom became aware of something going on furtively and silently about him. He looked around sharply, and caught the hall in the act of emptying itself of furniture and rugs and pictures. They were not positively going, perhaps, but rather failing to be there. The Gothic barometer, for instance, was there, before he turned to look at the red fox: when he turned back, the barometer was still there, but it had the appearance of something 0nly sketched against the wall, and the wall was visible through it; meanwhile the fox had slunk into nothingness, and all the other creatures were going with him; and turning back again swiftly to the barometer, Tom found that gone already.

And here’s Tom’s first experience of the garden.

There is a time, between night and day, when landscapes sleep. Only the earliest riser sees that hour; or the all-night traveller, letting up the blind of his railway carriage window, will look out on a rushing landscape of stillness, in which the trees and bushes and plants stand immobile and breathless in sleep – wrapped in sleep, as the traveller himself wrapped his body in his great-coat or his rug the night before.

This grey, still hour before morning was the time in which Tom walked into his garden. He had come down the stairs and along the hall to the garden door at midnight: but when he opened that door and stepped out into the garden, the time was much later. All night – moonlit or swathed in darkness – the garden had stayed awake; now, after that night-long vigil, it had dozed off.

The green of the garden was greyed over with dew; indeed, all its colours were gone until the touch of sunrise. The air was still, and the tree-shapes crouched down upon themselves. One bird spoke; and there was a movement when an awkward parcel of feathers dislodged itself from the tall fir-tree at the corner of the lawn, seemed for a second to fall and then at once was swept up and along, outspread, on a wind that never blew, to another farther tree: an owl. It wore the ruffled, dazed appearance of one who has been up all night.

This is gorgeous, gorgeous writing; mysterious, poignant, subtle…I could go on. And I wonder – which wondering isn’t to bag current children’s writers, editors and publishers, because I have been part of the industry – whether the book would find a taker in today’s market. It’s slow. There is a lot of description. It’s a thoughtful rather than an action-packed book. Time and memory and loss and change – the big themes of the book – are perhaps not what we’d think of as child-like concerns. The ‘climax’ – if you could call it that – is moving, but muted.

I think back to the writing of my three recent children’s books, all of which were set in the 1870s, and my wonderful editor’s reminders to always think of my (child) audience and not to get bogged down, to keep things moving, to watch my language. Long, difficult, challenging, archaic or even just old-fashioned words and phrases were all carefully considered and examined. Sometimes they could stay – but often there had to be a substitution or a re-formulation or an explanation. I’m not saying this was wrong, for it added to the readability of the novels, and very rarely did it seem worthwhile to dig my heels in.

I wonder, did I struggle with ‘difficult’ language as a child reader? If I did, I don’t remember it. I seem to have been able to have worked things out from context, or skipped over what I didn’t understand. After all, as a child, there’s so much in the adult word that you don’t understand, anyway. Are today’s child readers different to those of my generation? Yes and no, is probably the answer. So much (technology is the obvious thing) has changed, but perhaps some things – like curiosity and a sense of wonder – will never alter. I hope not.

Or perhaps by the time I am 95, like my beloved neighbour Margaret, I will probably be thinking, like her, that I just don’t recognise this world any more.

Tom’s Midnight Garden is probably my favourite book of all time — not children’s book, but book. I don’t remember struggling with the language or the pace as a child, I was completely captivated and returned to the book again and again. Perhaps repeated readings helped me to absorb the difficult words and concepts?

But I did notice, during a more recent re-read, that it was ‘slow’, and like you, I wondered if the current generation would persist with it. I haven’t let that stop me from recommending it in schools though 🙂

Children of Green Knowe, and The Chimneys of Green Knowe, were also special favourites, along with The Dark is Rising. Such lovely, strange and magical books. They are in my heart forever.

Some time this year I am planning to read all of Alan Garner’s books (now I finally own them all!) I think that will be an interesting adventure.

I think – I hope – that there will always be children who will enjoy this quieter kind of book. I see so many books in my job as a bookseller, and lots of them seem to be written, illustrated and designed to a noisy, out-there, look-at-me, best-selling formula. There’s always the newest Big New Thing, launched to us in the bookshops with posters, giveaways, dump bins, bookmarks, celebrity profiles (comedians, anyone?), and of course, it’s the first of a series… I’m not faulting the writers or publishers (or, not too much!) because publishing is a business and money has to be made or there will be no books on shelves at all. But I hope the gentle, thoughtful children’s novel won’t become extinct.

I’m also planning on re-reading Alan Garner’s books this year. And I must get hold of the Susan Cooper books again; I remember loving The Dark is Rising. And perhaps Penelope Lively, too. So many books, so little time!

I am a big fan of Quiet Books. Particularly Small Quiet Books. They curl into your heart and nestle there long after the showy, noisy ones have vanished like smoke after fireworks.

Yes, quiet and small are good. I’ve been finding a lot of books are just a bit too long lately… I don’t know if it’s just me, but I will get off to a rip-roaring start and then about 2/3 the way through my interest and attention just sags – and sometimes don’t even finish (though of course I read the last two or three pages, just to see how things have turned out). There are a few early Margaret Drabble books that are small and perfect. And great for carrying in a handbag and reading on the train.I am always on the lookout in the Oppy for slim Penguin spines!