Despite my anti-colonial and republican tendencies, I’m feeling quite English at present. It’s not just my obsession with the weather (it’s going to be 38 degrees here today, but a late cool change should see a drop of around 10 degrees during the night) but my reading. I’ve just finished six Barbara Pym novels in a row, and with each of them I’ve found myself trying on her heroine’s identities.

Despite my anti-colonial and republican tendencies, I’m feeling quite English at present. It’s not just my obsession with the weather (it’s going to be 38 degrees here today, but a late cool change should see a drop of around 10 degrees during the night) but my reading. I’ve just finished six Barbara Pym novels in a row, and with each of them I’ve found myself trying on her heroine’s identities.

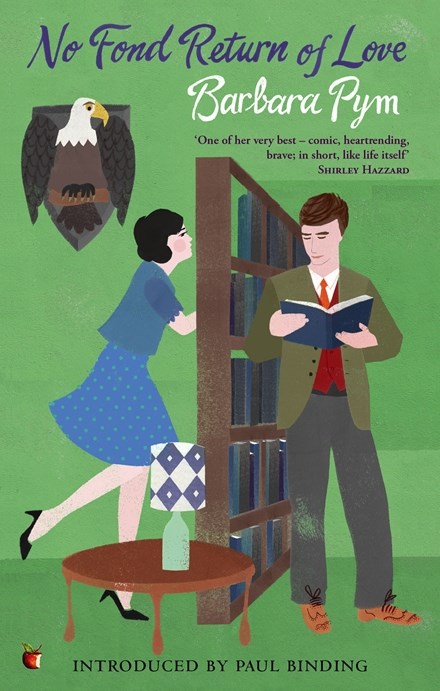

Could I be Dulcie, from No Fond Return of Love? She’s a tall, not-bad-looking but unfashionably dressed suburban spinster in her early 30s; a professional indexer, with a sharp and observant eye and an insatiable curiosity for her fellow beings; after a broken engagement, she’s indulging in a bit of mild stalking of an alluring (but married) professor.

Or Catherine, from Less Than Angels, a small, thin, rather bohemian Londoner, who thinks of herself ‘with a certain amount of complacency, as looking like Jane Eyre or a Victorian child whose head has been cropped because of scarlet fever’; a sharp and witty writer of short stories and articles for women’s magazines, whose anthropologist lover has deserted her for a younger and more adoring woman.

Or, from A Glass of Blessings, the beautiful and elegant Wilmet, a spoiled and under-occupied young woman whose idle hours are beguiled by involvement in the local church and the project of reforming the elusive, attractive ne’er-do-well brother of her oldest friend?

Like Jane Austen, Barbara Pym just did not write enough, so I read her novels again and again. For the comedy (I think they’re very funny books) but also for passages like this, from No Fond Return of Love:

If I had married Maurice, she thought doubtfully, I might have had a child, but the picture of herself as a mother did not become real. It was Maurice who had been the child. Theirs would have been one of those rather dreadful marriages, with the wife a little older and a little taller and a great deal more intelligent than the husband. And yet, although she was laughing, there was a small ache in her heart as she remembered him. Perhaps it is sadder to have loved someone ‘unworthy’, and the end of it is the death of such a very little thing, like a child’s coffin, she thought confusedly.

Barbara Pym is a sort of writerly heroine to me; it’s because, though the years between 1963 and 1977, when no-one wanted to publish her books (“too old fashioned”), she just kept plugging away. It was only when influential admirers Lord David Cecil and Phillip Larkin championed her work in the late 1970s that her fortunes revived. Her novels from the 50s and early 60s were reprinted, also her ‘rejected’ novels and even some early works. She also began publishing again.

The late novels – one of which was nominated for the Booker – lack the sparkle of the earlier ones; they’re sadder and wiser and perhaps more profound. But I confess that I do love the sparkle. They’re among my favourite books for comfort reading. They were hard to find in the early 2000s, and my copies, 1970s reprints bought second-hand, are falling apart now – however, a quick look on Booktopia shows that everything is back in print again, with enticing new jackets. Another revival.

Susan, can I confess that I have never read a single Barbara Pym novel? I feel sure that a great treat is in store for me. How wonderful to find a ‘new’ author with an untouched back catalogue heaped up like a dragon’s treasure.

… I didn’t even realise what I did just there.