It is my observation over many years that those who most powerfully resist convention quite peaceably accept the state of being reviled.

A woman leaves her marriage and her work for the Threatened Species Rescue Centre because she’s lost faith in them both. In the first part of the book, she returns to her home town in country NSW, in the Monaro. She’s burnt out, and wants to spend five days at a Catholic retreat house in a monastery run by nuns. It’s nothing flash. There’s basic accommodation and catering, solitude if she wants it. She was brought up as a Catholic, but she’s no longer a believer; she only has to attend the services if she chooses. Initially she’s full of discomfort and complaint; she sleeps poorly, the food is horrible, it’s cold. She starts going to the services, and she’s full of complaint about those, too. Bibllical mumbo jumbo. But gradually she changes, and at times is able to appreciate the beauty of the singing, the tranquility of the routine. She’s moved to tears by Communion; ‘It has to do with being greeted warmly by a stranger, offered peace for no reason, without question’.

She thinks a lot about her parents, in particular her mother. She was a greenie before her time, and so compassionate to others less fortunate, that a schoolmate once asked if she was a missionary.

And then she leaves, to return to the city.

On to Part II, the longest section of the book, and it seems that the woman has now been at the monastery for some (unspecified) time. There is no real plot. She takes part in the running of the place – cooking, shopping, cleaning, working in the vegie garden. A fellow student from her old high school, Richard Gittens, helps out around the place. The body of one of the order’s nuns, who was murdered in Thailand, is found, and arrangements are made to return the remains to the nuns. There’s Covid, and an infestation of mice. A ‘high profile nun’, an activist for many causes, Helen Parry, also a fellow student from the local school, comes to stay at the retreat. She was a prickly, difficult, unlikeable teenager and she’s the same as an older woman. Helen Parry and the narrator have a complicated history; she was once complicit in her bullying. The woman sifts through memories of country town life. The mice reach plague proportions. The woman thinks a lot about her mother, and school days, and right and wrong, goodness and kindness, compassion and forgiveness.

In part III, she thinks about those things some more. Especially forgiveness. She excavates more memories from her country town; the boy who shot and killed his parents, Helen Parry’s mother hitting and yelling at her outside the supermarket and Helen’s response. Her mother’s do-gooding (my phrase); visiting a woman suffering from depression, assisting the settlement of Vietnamese refugees. She thinks about the process of dying, and death – her mother’s, a friend’s, an anorexic teenager’s. She drives Helen Parry (always referred to by both names) around the town and realises that Helen’s mother must have been in and out of the local mental health unit.

And nobody in our town – not a teacher, a psychiatrist or doctor or nurse, not a schoolmate, another parent, not Mrs Bird nor my mother – had made a move to do anything about a schoolgirl left on her own in a housing commission flat, getting herself to school each day to be insulted and assaulted and despised, going home at the end of the day alone.

The nun’s remains are buried. Helen Parry leaves. The narrator thinks about her childhood dog’s death, and mother’s reverence for the earth. And that’s the end.

I’ve given a fairly full account of the novel, because I think it will indicate why I found Stone Yard Devotional initially so perplexing. What’s it about? Nothing’s happening? Is there a mystery, a drama, about the dead nun, or Helen Parry, or Richard Gittens? When will the plot kick in?

It doesn’t. It took around 150 pages for me to settle down, to accept that the book is what it is, and not want it to be anything else. It took that long for me to begin to read more slowly, not to race forward. To stop and think, to reflect on my own country upbringing as the unnamed narrator reflects on hers. The tragedies and hardships, accidents, illnesses and deaths. The unfairness of things. The kids who were routinely persecuted or excluded. The things I could have done, and didn’t. The way I still remember, after nearly 55 years.

The narrator dwells on grief, hers and others’. For losses endured (her parents, a friend) and the huge one – the climate crisis – that’s coming to us all.

And it’s not depressing. I loved the beautiful, spare, precise writing, the spiralling structure of memories and thoughts and observations, the rounds of work and effort, the gently piercing insights (nothing was laboured, it was all done slantwise). The way all those finely observed moments of monastery life and thought and memory add, detail by detail, to make a book of great weight and depth. It’s a quiet book; if it had a colour, it would be grey, a beautiful, delicate and calm pale grey.

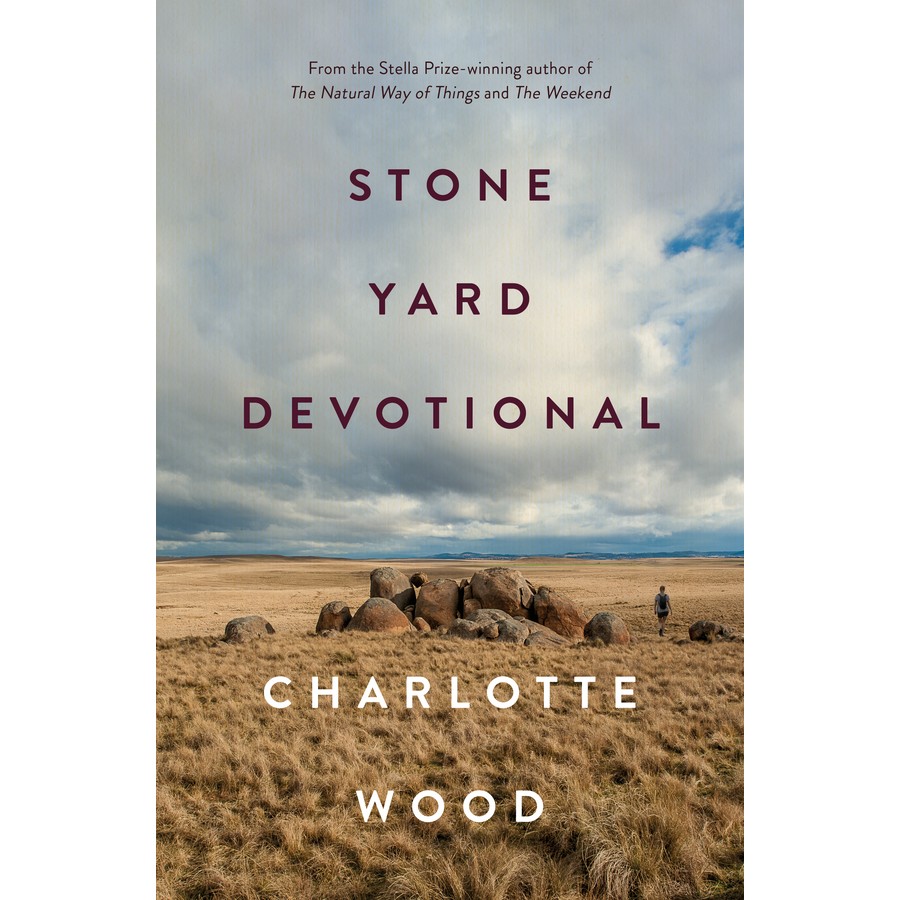

Driving across the surface of the high stony plains on my way there, I found the landscape’s desolation beautiful. My car had been seized now and then by the wind, and I had to grip the steering wheel to correct its movement across the empty road. The sweeping, broad structure of this land gently shifts from one plane int another, each sloping yet almost flat, like a shoulder blade. Although these plains bristle with a fine skin of pale grasses, they are almost as bare as bedrock, and I wonder if this is why I never came back, until now.

A moving, complex and thoughtful book, one to return to and think about.

I’m torn. Part of me very much wants to read this book (from your description, it reminds me of an Amanda Lohrey novel). I love nuns,and contemplation, and memory, and stories where not much happens.

But (this is going to sound very petty) I can’t do the mouse plague. I am absolutely phobic about mice and we had mice in our house recently… I just can’t! Maybe in a year or two when the memory has faded? But I’m afraid perhaps not even then.

Golly. OK, I’d avoid at all costs. It’s a bit visceral!

It’s only the mice that the book could do without. It is thoughtful, sensitive and reflective. It is an epic of introspection. Very beautiful.

This was my standout read this year. I couldn’t stop thinking about it…and that ending…the idea of burials, compost. I loved the two approaches to the calamity in the world. The narrator walks away from organisations supporting perceived solutions. Instead she stops. She enters a nunnery. She tries to cook better food, deal with mice. On the other hand Helen Parry is still waging battle but it is in the stopping, the observation of what is here in front of the narrator, the reflections… that is its own special work. And there is something in the idea of compost…that this is how the earth will process us too – that all we be turned over in the soil. I found so much relief in this.