Where do writers learn their best moves? They learn them from a technique I call X-ray reading. They read for information or vicarious experience or pleasure, as we all do. But in their reading, they see something more. It’s as if they had a third eye or a pair of X-ray glasses like the ones advertised years ago in comic books.

Where do writers learn their best moves? They learn them from a technique I call X-ray reading. They read for information or vicarious experience or pleasure, as we all do. But in their reading, they see something more. It’s as if they had a third eye or a pair of X-ray glasses like the ones advertised years ago in comic books.

This special vision allows them to see beneath the surface of the text. There they observe the machinery of making meaning, invisible to the rest of us. Through a form of reverse engineering, a good phrase used by scholar Steven Pinker, they see the moving parts, the strategies that create the effects we experience from the page – effects such as clarity, suspense, humor, epiphany and pain. These working parts are then stored in the writers toolshed with names such as grammar, syntax, punctuation, spelling, semantics, etymology, poetics and that big box – rhetoric.

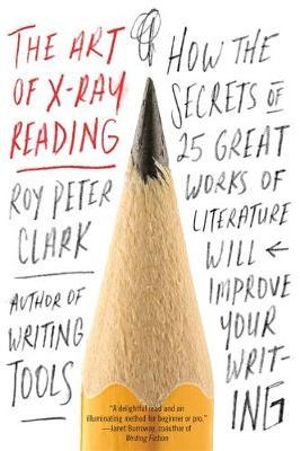

from the Introduction to The Art of X-Ray Reading by Roy Peter Clark: Little, Brown and Company, New York, 2016

Many years ago, when I regularly taught creative writing in community settings, I used to tell my students that the most important thing to do, if you wanted to write, was to read. All the time. Widely. Fiction, non-fiction, old, new, literature, genre, popular, for adults and teenagers and children. Perhaps I talked vaguely about how it was through reading that I began writing. I would have told them that reading was the way I learned about the shape of sentences and paragraphs, and how to create characters and scenes, and when was the best time for a surprise, an argument, a chase or a nice cup of tea. I learned what kind of books and writing I enjoyed, and worked out how to write that kind of book for myself. I always included excerpts from books to read and critique, but I really didn’t know how to show them, systematically, how to decode a piece of prose in a useful, instructive way. Nevertheless, some got it – and I think that they would have, anyway, without me.

But some didn’t at all. I wish I’d had this book to recommend, because it’s terrific. Texts spanning millennia – from Homer’s Iliad through to Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch – are not only lovingly investigated, but the obliging Clark also ends each chapter with a helpful list of ‘writing lessons’. And I loved the appendix, “Great Sentences from Famous Authors”. Apparently in 2014 the editors of The American Scholar selected “ten best sentences” from literature. I have no idea how you could choose ten, but it made me think about choosing a few “best sentences” from my current reading.

Dack’s Auto Court was on the edge of the city, in a rather rundown suburb named Ocean View. The twelve or fifteen cottages of the court lay on the flat top of a bluff, below the highway and above the sea. They were made of concrete block and painted an unnatural green. Three or four cars, none of them recent models, were parked on the muddy gravel.

The rain had let up and fresh yellow light slanted in from a hole in the west, as if to provide a special revelation of the ugliness of Dack’s Auto Court. Above the hutch marked ‘Office’ a single ragged palm tree leaned against the light. I parked beside it and went in. A hand-painted card taped to the counter instructed me to ‘Ring for Proprietor’. I punched the hand-bell beside it. It didn’t work.

The excerpt is from The Far Side of the Dollar by Ross MacDonald (Allison & Busby, London, 1988) and the narrator is the weary, cynical California private investigator Lew Archer. My X-Ray specs are still L-plated, but what I notice are the first couple of flat, matter of fact, factual sentences locating the auto court. We’ve got the natural elements of the scene, the bluff and the sea in competition with the built environment of highway, city, suburb. Archer’s jaundiced view of the place begins to come out in the details chosen for us when he describes the building and its surrounds – the concrete blocks are an ‘unnatural’ green (and yet green is the most natural colour one can think of); the cars are old; the gravel is muddy. A ray of light comes from the clouds, but there are no angel voices, no saints, no visions; instead, a ‘special revelation of ugliness’ comes from above. I laughed out loud at that. There’s only one palm tree, and it’s leaning and ragged; the hand-lettered notice is unprofessional and shabby. And to top it all off, the bell doesn’t work! Dack’s Auto Court is cheap, ugly, unloved – and, since this is a crime novel, the perfect setting for failure, despair and murder.

Apparently now primary school teachers are supposed to find ‘mentor sentences’ to illustrate how good writing works to their pupils. I’m not sure exactly what that entails!

But I’m also sure that it often takes several sentences, as you showed here, to layer a vivid scene. And it’s the little details that pack the biggest punch.