I spent most of yesterday at the Bendigo Writer’s Festival.

Out of a possible seven sessions, I attended four, and that was plenty. I think if I’d gone to all seven, my head would have exploded. And I would have been very cranky from hunger, as well.

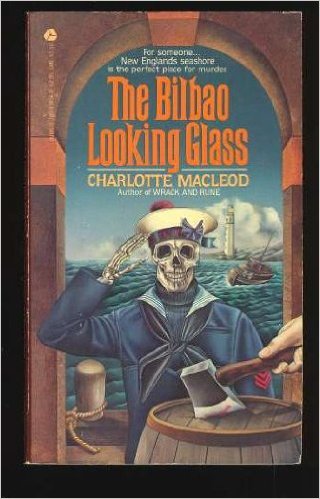

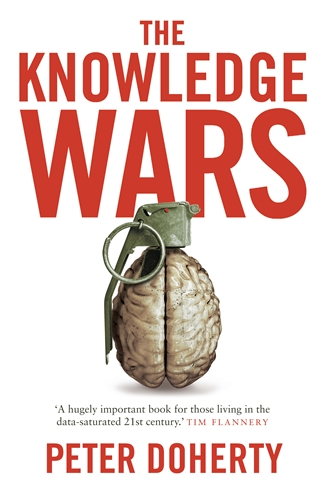

‘Knowledge is Power’ was with Peter Doherty, a Nobel Laureate and scientist who talked about his book, The Knowledge Wars. He had a dry gravelly voice, a dry sense of humour, spoke excellent, good-natured good sense and was far removed from the boffin, egg-head, somewhere-on-the-spectrum science nerd of myth and stereotyple. For such a serious topic – the discussion was mainly around climate change – there was much laughter. He was in conversation with education researcher Bronwyn Hinz. She was young, vivacious and bubbly (in a good way), and they made a good pair. She added much to the event.

‘Knowledge is Power’ was with Peter Doherty, a Nobel Laureate and scientist who talked about his book, The Knowledge Wars. He had a dry gravelly voice, a dry sense of humour, spoke excellent, good-natured good sense and was far removed from the boffin, egg-head, somewhere-on-the-spectrum science nerd of myth and stereotyple. For such a serious topic – the discussion was mainly around climate change – there was much laughter. He was in conversation with education researcher Bronwyn Hinz. She was young, vivacious and bubbly (in a good way), and they made a good pair. She added much to the event.

As did the obviously angry questioner at the end. Bristling with hostility, with a faux-humble preamble about an ordinary person like her questioning an eminent person like him, she bored in about what exact percentage of climate change is caused by human activities. Doherty’s answer was an example of how to do this stuff. When pressed, he gave her his own personal opinion – most! – but referred her, quietly and without fuss, to the science. Told her what to look at, and where to find it. Told her that it was the accepted science adopted internationally by goverments. Didn’t get cross. We all clapped.

‘An Affair of the Heart’, was with Kim Mahood, artist and writer, author of the award-winning Craft for a Dry Lake and now a new memoir, Position Doubtful. She grew up and has spent much time as an adult in remote areas of Western Australia.

‘An Affair of the Heart’, was with Kim Mahood, artist and writer, author of the award-winning Craft for a Dry Lake and now a new memoir, Position Doubtful. She grew up and has spent much time as an adult in remote areas of Western Australia.

What Mahood had to say about her art practice, her community projects involving maps, geography and Aboriginal understandings of place, her negotiations with people in the communities around their parts in her memoir was interesting and insightful but just missed giving me the sense of her passion for the place. Perhaps a stronger two-and-fro conversation would have opened my heart a bit more.

One session I queued up for – Stephanie Dowrick talking about her lifetime of spiritual inquiry – was full, and I missed out. Which turned out to be a good thing, for I was ready for a bit of fun. And leafing though her books on sale in the festival bookshop, I realised I’d forgotten my near-allergy to the genre of spiritual and self-help writing in which the author uses the word ‘we’ (as in, “How we feel about our own self…”) as if we’re cosily in this together. When the author is actually telling me her version of how it is for me.

Instead, I was delighted by ‘A Big Voice’. Which was Robyn Archer – the wonderful singer, performer, director of festivals, deputy chair of the Australia Council – who talked ten to the dozen in conversation with David Lloyd. It was like listening to a dinner party conversation with a witty, generous, kind and lively guest – don’t stop! I kept thinking. The audience joined in spontaneous applause when she suggested that every Ministry should have a desk for the arts. The Ministry of Defence, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs…

My last session had a Castlemaine connection as two of the authors live here. ‘Starting Over’ showcased three new-to-the-business authors talking to Scott Alterator about making a late start. Doug Falconer, who in a past life was drummer with Australian band Hunters and Collectors (and our neighbour), is in the throes of writing a novel. Sally Abbott, ex-journalist, now in public relations, who also lives in Castlemaine, won a prize for her unfinished manuscript Closing Down. She was given a contract by Hachette and is now in the process of editing. The other writer was Jerry Grayson, a much-decorated helicopter search-and-rescue pilot who’s published his first memoir Rescue Pilot:Cheating the Sea and is working on his second book about his experiences as a film pilot.

The two writers I’d wanted to see and hear – Helen Garner and Cheryl Strayed – had cancelled. I was disappointed. I’d just re-read Garner’s The Spare Room, as well as her new book, Everywhere I Look, was full of admiration for her sharp, clear vision and language; I wanted to hear her voice. And I’d been blown away by Wild. It was very bad luck for the two of them to cancel. (Confession: I wouldn’t have bought the pass if they hadn’t been on the bill.)

It was a long day of culture. I am all cultured out.