Being a creature of habit, when I’m at work I have lunch in the same cafe most days. It’s a small(ish) town – around 7,000 people, I believe – and so you get to know the people who serve you. Like the lovely Davina. She’ll occasionally lend me a book, and they’re often not the kind of book I normally read (which is a good thing as it expands my horizons). Recently she handed over a Martin Cruz Smith thriller set in Venice during WW2 and a rather insipid historical romance.

Being a creature of habit, when I’m at work I have lunch in the same cafe most days. It’s a small(ish) town – around 7,000 people, I believe – and so you get to know the people who serve you. Like the lovely Davina. She’ll occasionally lend me a book, and they’re often not the kind of book I normally read (which is a good thing as it expands my horizons). Recently she handed over a Martin Cruz Smith thriller set in Venice during WW2 and a rather insipid historical romance.

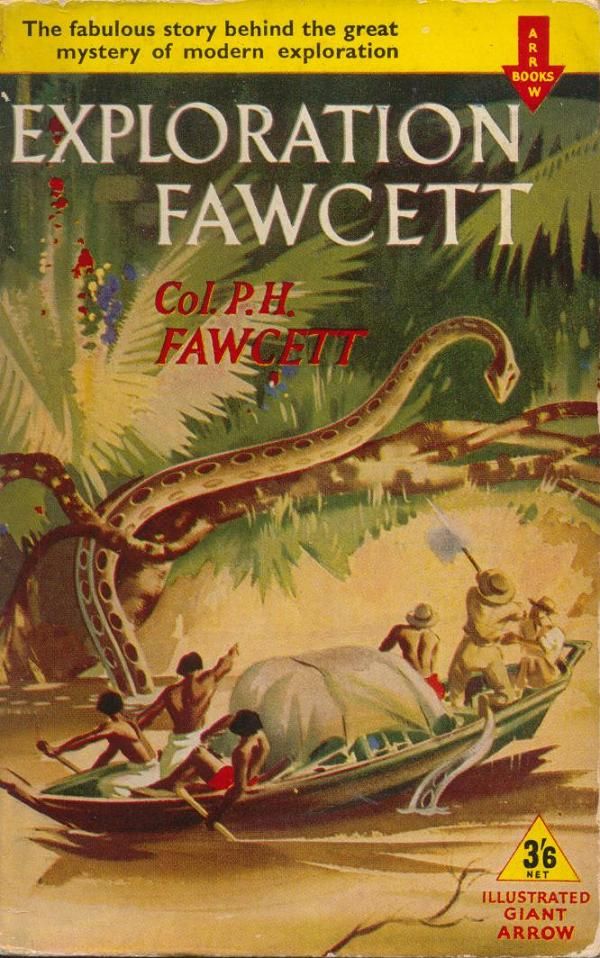

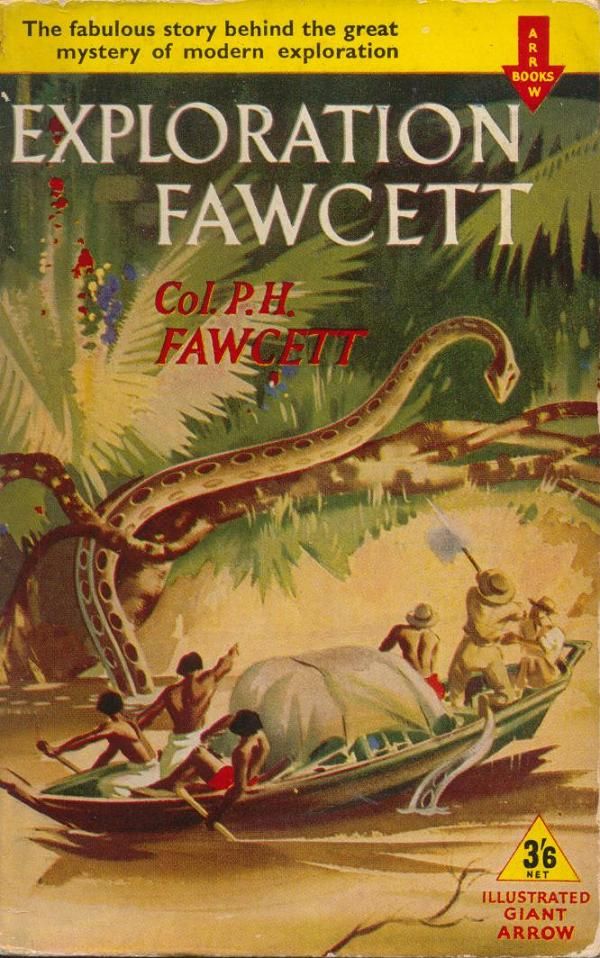

But the wild card was an unexpected and unexpectedly riveting ripping yarn called Exploration Fawcett. The cover says it all. Intrepid explorer, geographer and cartographer Lieutenant-Colonel Percy Harrison Fawcett first set off in the early 1900s for South America. Before and after WWI, he worked and travelled in Peru, Bolivia and Brazil mapping and delineating borders, but he always wanted to mount his own expedition in search of a fabled ‘lost city’ in the jungles of Brazil.

I could have hated this book, for with all of the imperial arrogance of his era, Fawcett never questioned the project of “exploration for exploitation” – be it minerals, timber, or rubber – in these vast but already inhabited territories. His idee fixe was that somewhere, hidden in the jungle, he would discover the remains of a lost civilization belonging to a superior, lighter- or even white-skinned race – the eugenicist theory fashionable in his day being that the more highly evolved peoples have paler skin.

Yet for all this, he was unusual in being not only fascinated by but sympathetic to the indigenous peoples he met during his travels. He not only sought to communicate with them; he was patient, courteous and actually thought there was something he could learn from these so-called “savages”. A constant theme is his shock and disgust at the behaviour of Europeans – miners, rubber tappers, ranchers and settlers – and their brutal treatment of enslaved workers, the massacres of forest tribes, the wanton cruelty and destruction of culture, language, ways of life.

Exploration Fawcett reads a bit like one of Michael Palin’s Ripping Yarns – Across the Andes by Frog. Percy Fawcett was a true obsessive – utterly mad actually – with demented stiff-upper-lip fortitude and courage that ignored heat and cold and illness and injury in his pursuit of his quest. When I put the book down to go to sleep at night my mind was a National Geographic extravaganza of swamps, jungles, mountain passes, deserts, lakes and rivers, with strangling vines and cacti and thorn bushes and giant trees, swarming with rattlers and enormous anacondas and a multitude of other snakes, as well as monkeys, panthers, parrots, condors, alligators, piranhas, not to mention ticks and ants and stinging insects galore. And indignant tribes, armed with bows and arrows against guns and disease.

The book was edited, with a prologue and epilogue by his son, Brian Fawcett. Percy Fawcett died in the Matto Gross of Brazil in 1925 – or that’s what we must assume, for he simply disappeared into the jungle, along with his eldest son and another young man. The bodies were never found.

I found myself thinking about his wife and remaining son and daughter. Percy died in his mid-fifties; he’d only ever spent ten years with his wife. He took their son – a young man in his early twenties – with him on the final fatal trip. And his son’s friend, too.

The dedication reads:

The lot of the one left behind is ever the harder.

Because of that – because she as my partner in everything shared with me the burden of the work recorded in these pages – this book is dedicated to my wife

“CHEEKY”.

I wonder what Cheeky actually thought about it all. Perhaps there’s a novel in it…

“…just because you love something you cannot make it stay.”

“…just because you love something you cannot make it stay.”