It’s six months since we visited a kitchen show room in nearby Bendigo to choose our cupboards and bench-tops and knobs. It’s five months since a handyman came to rip out our old kitchen. It was shortly before Christmas that the incorrectly cut stone bench-top was replaced, and a range-hood (left out of the initial plan because I didn’t realise that it was the same as an extractor fan) installed. Our old kitchen was a shabby 1970s affair, but we wouldn’t have bothered replacing it if had been able to accommodate a dishwasher. We (well, it was actually foolhardy me) reckoned that you could just cut the end off a cupboard and book in the plumber and it would be done. But no. It’s not that simple. As I have since found out, in the world of home renovation, it almost never is.

It’s six months since we visited a kitchen show room in nearby Bendigo to choose our cupboards and bench-tops and knobs. It’s five months since a handyman came to rip out our old kitchen. It was shortly before Christmas that the incorrectly cut stone bench-top was replaced, and a range-hood (left out of the initial plan because I didn’t realise that it was the same as an extractor fan) installed. Our old kitchen was a shabby 1970s affair, but we wouldn’t have bothered replacing it if had been able to accommodate a dishwasher. We (well, it was actually foolhardy me) reckoned that you could just cut the end off a cupboard and book in the plumber and it would be done. But no. It’s not that simple. As I have since found out, in the world of home renovation, it almost never is.

I’m not a natural at Home Beautiful. There’s so much stuff you have to keep track of. Endless decisions about very small details. Purchases. Tradespeople. Things you’re meant to know about, like the wiring and where the waste water exits the building. You have to care enough about the colours of tiles and reconstituted stone and melamine joinery so that you can choose from a bewildering number of alternatives. I won’t say it’s been hell. That would be ridiculous in a world where millions of people are not only without kitchens, but without roofs. But it’s been a journey, and a frustrating, time-wasting, delay-ridden one. Friends kept saying – we kept saying this to each other, too – “But you’ll love it when it’s finished.” Well, we shall see.

Yesterday the tiler came to affix the last five tiles. The plumber connected the gas to the cook top. And now – in perhaps the lengthiest and yet tiniest kitchen renovation on record – my husband’s just cooked the inaugural meal. Baked beans on toast with fried eggs. (It’s not to be sneezed at – the perfect Saturday night dinner on the first really cold night this year). I’m planning roast chicken tomorrow, but I think it will take a lot of dinners before it feels like “my ” kitchen. It’s probably the absence of grot and clutter – at present we’re fanatically wiping and rinsing and putting away – but a little time will take care of that.

All of this made me think about those perfect kitchens that feature in interior design books and TV shows and magazines. Home Beautiful kitchens. The ones with only a basket of quinces on the bench top, or else an artful platter of heirloom tomatoes. They may be stainless steel quasi-laboratories, or so-called “country style’ or retro or mid-century or whatever else is in vogue, but these shiny clean spaces usually have something in common; they don’t appear to be actually cooked in. Lived in. How busy the stylists must be, stowing tea towels and oven mitts and food processors and t0asters and the compost bucket.

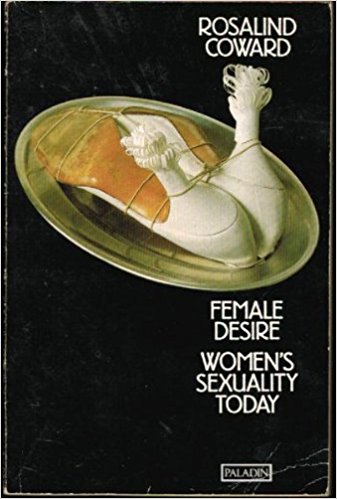

My 1984 book of essays, Female Desire: Women’s Sexuality Today by Rosalind Coward, is dated in some ways (how could it not be?) but not the chapter called Ideal Homes.

This regime of imagery represses any idea of domestic labour. Labour is there all right, but it is the labour of decorating, designing and painting which leads to the house ending up in this perfect state. We hear about how much the wallpaper cost and how much it cost to get the underlying wall in good condition. We don’t hear about how long it took for some woman to get the room tidy, or who washed the curtains. But the photographs only show the ever-tidy, clean and completed home. The before and after imagery endorses the joint work of couples, the husband and wife who plan, design and decorate the house. The suggestion is that together men and women labour on their houses. The labour is creative and the end product is an exquisite finished house-to-be-proud-of. Domestic labour, the relentless struggle against things and mess, completely disappears in these images. The hard and unrewarding ephemeral labour usually done by a woman, unpaid or badly paid, just disappears from sight. Frustration and exhaustion disappear. Instead, a condition of stasis prevails, the end product of creative labour.

I had the great good luck to be raised by a stay-at-home dad. Many women of my generation had mothers with ferocious standards of housekeeping, up to and including the requirement for a toilet so clean you could almost eat from it. For some of them, there’s a residual guilt that their houses don’t measure up to Mum’s ideal. This was not my father. His emphasis was on comfort and good food. I remember being shown how to sweep dirt under the mat when visitors were imminent. Don’t take that to mean he despised domestic life; I think he loved it. As I do. He was aware of the large and small ways in which he was responsible for this machine/organism we call “home”. I gained a sense of the seriousness of the task. A well-run home is important to everyone – the adult partners and the children. You could say, to society in general. But it’s still seen as women’s work. And – how wearying this is! – still so undervalued.

However uncritical women may be of bearing the responsibility for the home, it is a rare woman who has never experienced home as a sort of prison…bearing the awesome responsibility for the survival of young children, or torn by commitments to work and children, the home is often a site of contradiction between the sexes, not a display cabinet. Even in the most liberated households, women are well aware of who remembers that the lavatory paper is running out and who keeps an eye on what the children are up to.

Female Desire; Women’s Sexuality Today by Rosalind Howard, Paladin Books, London, 1984