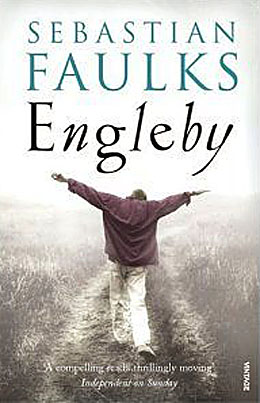

This is our Book Club choice for this month, and I think I can guarantee it’s going to create a lot of discussion. It might even be “love it or hate it”. We shall see.

Mike Engleby narrates his own story with what seems like total candour.

Mike Engleby narrates his own story with what seems like total candour.

When the novel starts, he’s in second year at Cambridge University. It’s the ’70’s; he won a prize to go to university, after winning a scholarship to a minor public (read: private) school. He’s not posh; his family are working-class and poor. He drinks a lot. He takes prescription and recreational drugs. Crime? He does a bit of dealing, a bit of stealing, but nothing violent or sexual.

He’s highly intelligent, with a phenomenal memory. Observant. He’s got a wide general knowledge – politics, history, literature, music – and seems to soak up information like a sponge.

But quite quickly, the reader realises he’s an unreliable narrator. He’s also seriously creepy.

Engleby’s a stalker.

He’s become obsessed with another student, a girl called Jennifer. He watches her, attends the same clubs, starts going to one of her classes. She’s been cast in a film, and he manages to inveigle his way into the shoot in rural Ireland. He thinks he has some kind of relationship with her, but it’s mostly imaginary. When she vanishes, he’s the prime suspect.

Repellent, yes? Well, yes and no. Mike’s account of his dead father’s violent abuse, and the sustained bullying he experienced at his school are truly horrifying. There’s a sadness in his attempts to connect with Jennifer and in his solitary pub crawls and time spent hanging about on the fringes of student life. He knows there’s something not quite right with him, and at times, he’s perceptive enough to describe his mental state.

As in this scene. He has travelled alone to Istanbul:

It was one a.m. in the grey sodium light with the wailing music and the black ground with its spattered chewing gum and cigarette ends. I had started to pay too much attention to things. It was almost as though I could see right through them into the molecules that made them. And that awful music. I suppose my wind was trying too hard to get a grip on this place, to anchor it for me, because I had the strong impression that I was really outside time or place, that the hostile otherness of my surroundings was such that my own personality was starting to disintegrate. I was vanishing. My character, my identity, had unravelled. I was a particle of fear.

I guess I was a little lonely then.

In general, in less extreme circumstances, lonely looks after itself. It helps you develop strategies that reinforce it. The comfort of the dark cinema and the company of the screen actors prevent you from meeting anyone. Lonely’s like any other organism: competitive and resourceful in the struggle to perpetuate itself.

Engleby is not charged with any crime relating to Jennifer. He goes on to become a successful journalist. He forms a relationship with a woman, and they even move in together. She has a young daughter, and he enjoys her company. Life’s going well. Warning, there’s a spoiler here – but most readers will guess this is going to happen.

A body is discovered in a drainage ditch. And it all unravels.

Close to the end of the book, when Enderby is in his 17th year of imprisonment/confinement in an institution for the criminally insane, he reflects on his life and the reader gets a sense of what made him.

Once I saw a mother in a supermarket in Paddington – an obese, poor woman with bare legs and a small child who was making a noise. She swore at him and slapped him in the face, which only made him howl more. It wasn’t her fault really; she was clearly exhausted, broke and stretched to snapping point. But I knew that when she got the child home she’d beat him more, and if there was a father (a bit unlikely) he would hit him too.

And that child would slowly ascend towards full awareness in a world whose sky was violence and horizons were fear. And however resourceful he was, however patient and fortunate in the events of his life that followed, he was like a creature in a nest of imprisoning boxes who could never really break free. That was his world and any attempt to persuade him that it was merely a ‘subjective’ or ‘individual’ experience could never convince him.

And all of us, I think, are like him.

Dense with multiple themes, the book is disturbing, tragic and at times weirdly funny (Engleby’s experiences with the legal and mental health systems are beyond absurd). When towards the end of the novel, Faulks takes us outside the closed world of Engleby’s deluded mind, his disconnect from reality becomes even clearer. Weirdly, I found the section where his Cambridge friend, Stellings, describes him as others saw him was almost heartbreaking.

Poor Jennifer. Poor Engleby.