Our son came up on the weekend, a Father’s Day visit, and he brought with him a couple of issues of the Quarterly Essay for me to read. I have to confess that these days, my news media/current affairs reading is pretty slight. Each day I skim the Melbourne Age and the Guardian, which gives me British as well as Australian articles and commentary. I gave up my New York Times habit over a year ago, after overdosing on American politics during the Trump presidency – but an astonishingly cheap deal for the New Yorker got me a very smart tote bag and a digital subscription. Though I don’t always make the best use of it, I do appreciate the daily newsletter that pops into my inbox. It often prompts me to read something I didn’t even know I was interested in. Or to read an American take on something I care about, like literacy.

The Rise and Fall of Vibes-Based Literacy by Jessica Winter, in the September 1st issue, got me thinking (again) about my own struggles with teaching children to read.

By ‘vibes-based literacy’, Winter means the method called in the US ‘balanced literacy’. It’s also often known as ‘Units of Study’, ‘Lucy Calkin’ (after the influential educator who wrote the aforementioned) or simply as ‘Teacher’s College’ because it was so widely taught to student teachers. In a (very little) nutshell, children are helped to develop a range of cueing strategies and memorise high-frequency words. It’s much the same as what we called the ‘whole language’ or ‘whole word’ approach, back in the day when I was at Melbourne Teacher’s College. Phonics and other explicit instruction in decoding strategies were very much frowned upon.

According to Winter, since the 1980s Lucy Calkin’s approach has dominated American schools and in fact, was the officially mandated teaching method in many districts. This, despite the “long-standing consensus among researchers that intensive phonics and vocabulary-building instruction—an approach often referred to, nowadays, as the “science of reading”—are essential.”

She continues: “There has never been much peer-reviewed research to support Units of Study or other balanced-literacy curricula. In 2020, the education nonprofit Student Achievement Partners published a meticulous vivisection of Calkins’s program: “there are constantly missed opportunities to build new vocabulary and knowledge about the world or learn about how written English works,” the authors noted. “The impact is most severe for children who do not come to school already possessing what they need to know to make sense of written and academic English.”

Which had me thinking about my prep grade at a small rural primary school way back in 1985. I’d had a grade 2-3-4 f0r two years, and the principal decided it was time to move the staff around. I have the greatest respect for good early childhood teachers, mainly because I wasn’t one and I know how hard it is. Worse, I was drastically under-prepared to teach reading because I had no idea where to proceed with the children who weren’t naturals.

Fortunately most of them seemed to just ‘catch’ reading. Some of them had difficulties but eventually managed to master their readers or the little books we made in the classroom. And a very few made very little progress at all under my watch. Like the little girl I’ll call Annie-May.

My principal gave me ten minutes a day to do intensive reading practice with Annie-May. I had no idea what I was supposed to do, really. So I sat her on my knee, and we ‘read’ books together. She was supposed to predict the text, using the pictures as clues. She was supposed to easily recognise words like ‘the’, ‘and’ , ‘she’ and ‘him’ and build up a wider vocabulary bank of memorised words like ‘cat’ and ‘dog’ and so on. She was supposed to learn to associate reading and books with enjoyment. Which she did, in a way. After one session, when I thought we were beginning to get somewhere, Annie-May turned to me and said (and yes, she did speak like this), “Dat was a nice little tuddle, Miss Dween.”

In later years, thinking about Annie-May, the youngest of a family of six children from a farming family – busy, financially stretched, with little time for reading and books – I wonder if she ever learned to read fluently. Was there a window of opportunity there, in preps, that was missed because I had no idea? I have to set against my pangs of guilt, the image of the happy little girl who’d had some precious moments of quiet time with her teacher. A nice little cuddle.

Good vibes…but as far as literacy is concerned, a fail.

This is a highly charged topic for me, having suffered along with my eldest as she struggled to master reading. We threw everything at it and not much stuck — explicit phonics, flashcards, Reading Recovery, an SRA program that cost a fortune and achieved nothing other than making Al cry, several tutors… It was a painful few years.

I first suspected something was wrong in Grade 1 but her teacher at the time basically laughed at me and said, ‘No way, if she had dyslexia, she would be reversing her letters and she isn’t.’ I don’t really blame him, but he just had no idea.

I can imagine how distressing it was for all of you, Kate. I have a friend whose daughter was only diagnosed formally with dyslexia in Year 7. By then she had all kinds of learning issues, and rock-bottom confidence.

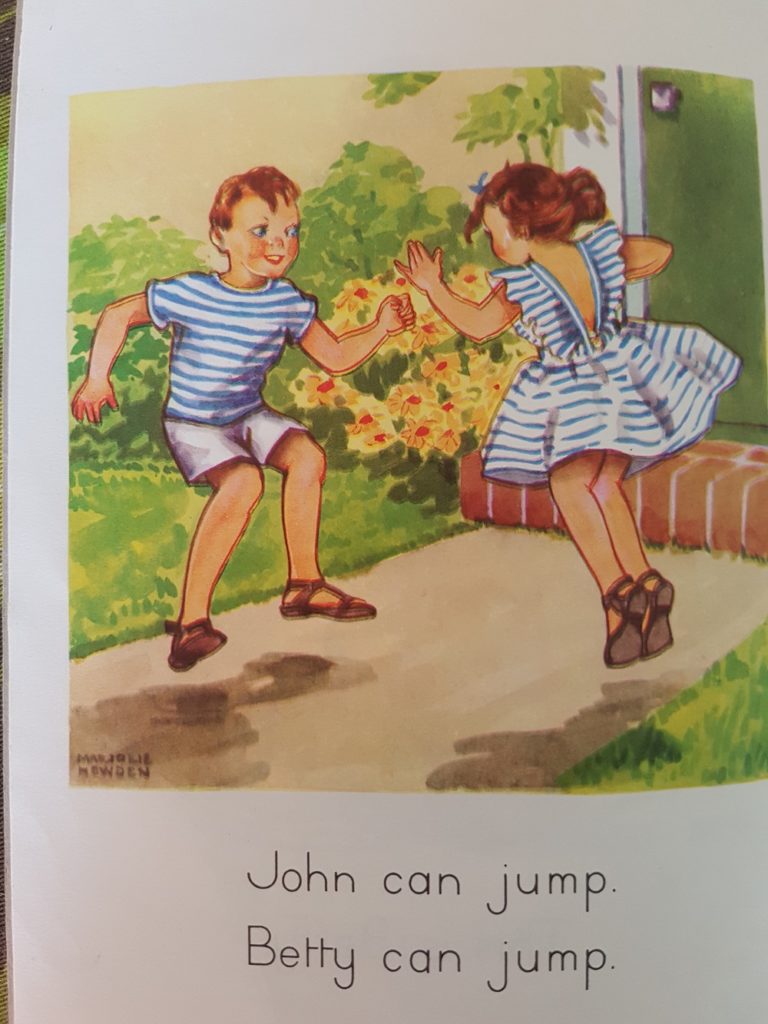

And it’s somewhat charged for me, too. I didn’t learn to read until Grade 2. Two years of remedial reading – I even ‘repeated’ Preps – and finally my mother took things into her own hands. Once I got it, I couldn’t stop reading, but I still remember feeling stupid and bewildered. I blame John and Betty, the most boring kids on the planet. Who would want to read about their tedious lives?

Oh my God, the ‘readers’ were a special torture all their own. SO BORING, why would any child even want to look at them, let alone try to decipher them? We were issued with ‘reading diaries’ which we were supposed to fill in every night as we struggled over these bloody awful ‘books’, but meanwhile I was reading to her and she was listening to audiobooks every night, none of which counted. In the end I just refused to cooperate (most unlike me, I am very law-abiding).

The ultimate irony is that it was the audiobooks, none of the other formal training, that finally provided the break-through.

I’d like to think things have improved in schools in recent years but who knows?