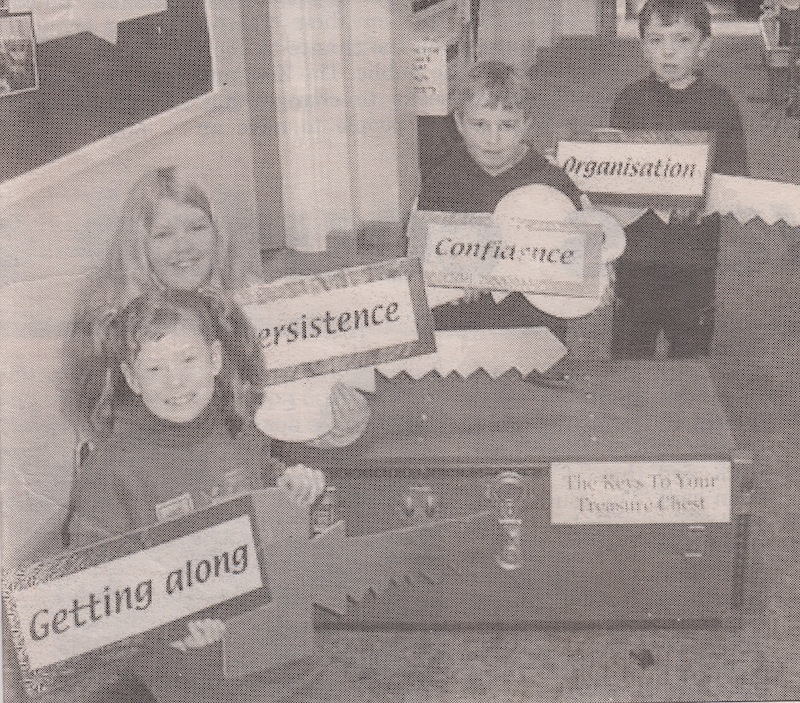

That’s my son, Lachie, at the top of the photograph, holding this big cardboard key and looking bewildered. It was taken 14 years ago, when he was in Grade 1. What 6-year-old even knows the meaning of ‘organisation’? Not my poor little pet, that’s for sure. I’m nearly 60 and I’m still learning.

That’s my son, Lachie, at the top of the photograph, holding this big cardboard key and looking bewildered. It was taken 14 years ago, when he was in Grade 1. What 6-year-old even knows the meaning of ‘organisation’? Not my poor little pet, that’s for sure. I’m nearly 60 and I’m still learning.

Generally, I think I do a reasonable job – manage to pay bills on time, keep documents more or less filed and know where the passports are. But, faced with the imminent NFY (that’s New Financial Year, in case you didn’t know) and the purchase of a yet another financial year diary, I looked at last year’s and realised that I scarcely used it. Clearly, another form of organisation tool is required.

Intrigued by an article in one of the weekend magazines, I went online to find out about the Bullet Journal. I found a delightful young Asian-American woman called Wendy doing a show-and-tell. I just love stationery, and so does Wendy, so I enjoyed this every much. She uses a special journal with dots instead of lines, however some people like squared paper, and others make do with old-school lines. You can use this one book as a journal, a diary for appointments, a goal-setter, to-do list and scrapbook. You number the pages, you make lists, you make an index. You have a little system of symbols to add to your notes – for instance, if you missed making that call to Sandro today, you can “migrate” that task to tomorrow. A useful tool indeed, and – amazingly, in this world of so many apps – the revolutionary thing about it is that it’s ANALOG.

Yes, I am having a go. It’s a notebook. I was less than amazed (sorry, Wendy) but actually, funnily enough, inspired. Every year, for the past 10 years, I’ve bought the same Collins Vanessa diary. This year, I’ve got a spiral bound student notebook from Typo and I’m experimenting. The simple act of sitting down at the start of the week and listing the things I have to do and the things I want to do – finish the novel, buy carrots, apples and a litre of milk – is proving helpful. Crossing jobs off as I complete them is almost joyful.

I got the carrots, apples and milk. The novel…

That’s another story.