You can’t judge a book by its cover.

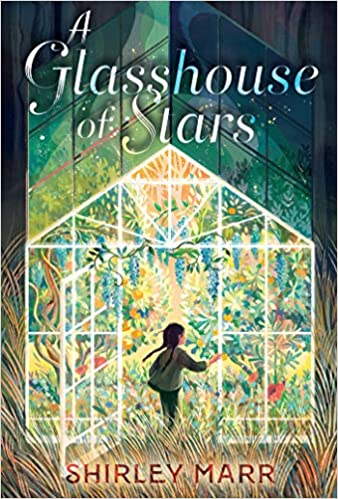

The really lovely illustration by Cornelia Li for A Glasshouse of Stars speaks of sweetness, magic and whimsy. Which are certainly here in Shirley Marr’s new junior novel. But it’s a much meatier story than you might expect.

Meixing Lim, her father and pregnant mother have been left a house in the New Land by First Uncle. As soon as they arrive from their island home, problems arise and multiply. Everything is different and strange; language, food, money, school, shops. There’s racism to contend with. Anti-Asian posters are plastered in the street; her father can only find a labouring job, and he’s bullied on the site. Money is tight, and her parents begin to quarrel. Stressed and anxious, neither have much time for their daughter’s fears and worries. Meixing’s trying to cope with the new language and a vastly different school system, as well as nasty girls and no friends, but it’s a struggle.

However when she comes home, another reality awaits.

The house, which Meixing names Big Scary, seems to be alive. Rooms change in size and colour and location according to mood and need; a window is an eye, the carpet is fur. The abandoned glasshouse in the garden is even more magical.

The first thing you think is that it is much bigger in here than you thought it would be…

Spread out before you is an entire orchard. You stare in surprise at what is in front of you…

A pink serpent, looking for all the world like it escaped from the neon glow of Big Scary’s wardrobe, hisses at you as you approach. You take a step back and it disappears into the branches of a tree. You aren’t scared because the sun is spreading reassuring rays over to you from the east. This is a sun you can stare straight at, and she has a beautiful face.

The glasshouse contains the sun and the moon and the stars, First Uncle himself and a library of magical seeds. It’s more than a bit psychedelic, but makes perfect sense. Meixing is (adult-speak here!) suffering trauma, dislocation and loneliness. She’s a child burdened with outsize responsibilities and challenges. She’s also brave and very imaginative. Her magic greenhouse is healing, consoling and uplifting.

For all the beauty of the magical greenhouse, there are some dark and difficult themes. Meixing’s family endures a shocking tragedy, her mother’s mental health unravels, there’s racism and bullying – including an attack on Meixing and her mother – and an unplanned home birth. There’s also a lovely optimism. A kind teacher, who makes a real difference. A principal who believes Meixing and Kevin rather than the white girl. A firm friendship with Kevin and Josh, also from immigrant families. The loving embrace of family (those amazing Aunties!). And the magnificent power of creativity and imagination.

At the end of the book, Meixing says:

At the end of the book, Meixing says:

When Big Scary is sad, she shrinks. When she is happy there is no limit to how big she can get. I have realised she is only a reflection of ourselves. She is not prefect, but she is only human. I am thinking of changing her name to Little Scary.

I have a magical greenhouse in the backyard that is filled with magic seeds of the imagination. You only need to plant them for ideas to grow. I go there when I’m feeling sad. I’m not scared when it gets dark inside, as that’s when the stars shine the brightest. Maybe one day I won’t need to go there any more, but I hope that I always need to dream. Even when I’m an adult.

Shirely Marr has written a really special book, blending the trippily magical with a gritty immigrant story. I won’t be surprised if A Glasshouse of Stars wins numerous awards; it deserves to be widely read and appreciated.