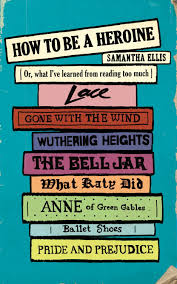

More reading about reading. Last week I finished How to be a Heroine;(Or, What I’ve Learned from Reading Too Much) by Samantha Ellis and it got me thinking about the heroines of my childhood. A reader, a bookworm, living much of the time in word worlds, I naturally pictured myself as the heroine of my own story. Doesn’t everyone?

More reading about reading. Last week I finished How to be a Heroine;(Or, What I’ve Learned from Reading Too Much) by Samantha Ellis and it got me thinking about the heroines of my childhood. A reader, a bookworm, living much of the time in word worlds, I naturally pictured myself as the heroine of my own story. Doesn’t everyone?

No, apparently. Years ago I made some horrible vain remark to the effect that I was glad I had my ankles are slim, for no heroine ever had thick ankles.

“What on earth are you talking about?” said my friend. She thought I was weird. “Heroines are in books. They’re not real.”

My reading project is still to read something old and something new, but some of the old ones will come from my childhood reading because I’m interested in those heroines that helped form me. This week I re-read Little Women.

First published in 1868, it’s an antique. So is my copy – pictured to the left, with cover and many lovely illustrations by Shirley Hughes. It’s the one I first read when I was around 10 or 11. I wondered if I’d find it unreadable, but I just gobbled it up, finishing the whole thing in two or three sittings. I found the language easy and readable, the characters engaging – especially Jo, of course. It’s sometimes funny, sometimes touching, and a wee bit sentimental. I shed a little tear when Beth defrosted old Mr Laurence next door and when she caught scarlet fever. The baby died in her arms! And of course Jo, with her intelligence, ambition and wild, coltish energy, is a living, breathing delight. But…

Yes, there’s a but. According to Ellis, it’s ‘unbelievably preachy.’ She reckons that every page ‘is rammed with endless, intrusive moralising’, and writes that ‘I never realised before that in Little Women, each March sister is tamed, one by one, part from Beth, who doesn’t need taming because she is a personality-free doormat. Which apparently is the ideal.’

Not quite. The ideal, stated by Mr March when he comes back from the war, is ‘a strong, helpful, tender-hearted woman.’ But I agree with Ellis that there IS lots of very explicit moralising. The Pilgrim’s Progress is mentioned over and over as the model for life’s journey.

Alcott has chapters that deal with Meg’s (pretty harmless, actually) vanity, Jo’s willfulness and temper and Amy’s selfishness. Beth, who is pathologically shy and at 14 still plays with dolls, is quiet, sweet and helpful, but even she gets a harsh lesson when Marmee decides to teach them that all play and no work is no fun either. No one feeds Beth’s canary, and she finds it ‘dead in the cage, with his little claws pathetically extended, as if imploring the food for want of which he had died.’ A bit harsh, Marmee!

What makes Little Women (and many other 19th and early- to mid- 20th century children’s books different to most published today is that Christian morality is front and centre.

But then, I read somewhere that Stephenie Meyer’s Twilight series was really one long Mormon tract on sexual abstinence.