A few days of sweet and nostalgic re-reading last week; The Painted Garden by Noel Streatfeild and The Rescuers by Margery Sharp. I loved them both when I was a child; reading was my ‘happy place’ and these two were re-read many times.

I’m always slightly nervous about beloved childhood books disappointing on an adult reading. I expect them to be dated, that’s not a problem. What is problematic for me is when the racism, sexism and class-based prejudice really stick in my craw. And that happens sometimes, even though I generally regard these books and these attitudes as basically artefacts from another time and another world.

(An example: last week I also tried to read an Agatha Christie novel, A Murder is Announced which was first published in 1950. I went through a Christie phase in my mid-teens, and was spellbound; this time, I wasn’t able to even get half way through. Christie may have been trying to show what horrible people her characters are, but their constant references to ‘foreigners’ as greasy, weaselly, dishonest, hysterical and prone to exaggeration led me to abandon ship even before Miss Marple came on board to solve the mystery. And the whole thing was so snobbish! Besides, if you’ve seen the TV series, you know who did it.)

The Painted Garden didn’t disappoint. Hooray! It sees an English family, the Winters, relocate to California to stay with their Aunt Cora. It isn’t a holiday. The father, John, needs somewhere in the sun to recover after a nervous breakdown caused by killing a child in a car accident. How’s that for heavy? The three children are all not keen, for different reasons. Rachel, a ballet student, is missing out on a role in a big ballet; Tim, a piano prodigy, is missing out lessons from a famous concert pianist, and Jane, who wants to be a dog-trainer, is just going to miss Chewing-gum, her dog.

The Painted Garden didn’t disappoint. Hooray! It sees an English family, the Winters, relocate to California to stay with their Aunt Cora. It isn’t a holiday. The father, John, needs somewhere in the sun to recover after a nervous breakdown caused by killing a child in a car accident. How’s that for heavy? The three children are all not keen, for different reasons. Rachel, a ballet student, is missing out on a role in a big ballet; Tim, a piano prodigy, is missing out lessons from a famous concert pianist, and Jane, who wants to be a dog-trainer, is just going to miss Chewing-gum, her dog.

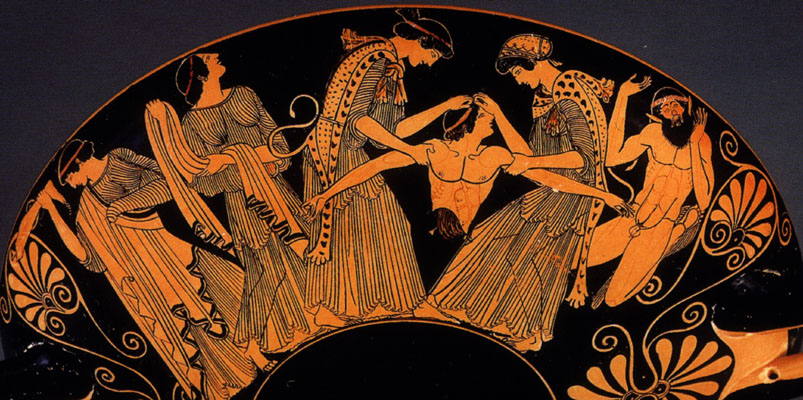

But things turn out fine. John gets better. Tim, in his search for piano to practise on, makes friends with the piano-owning Antonios, who run a drug store, and gains a spot on a Hiram P. Schneltzworther’s radio show. Rachel is befriended by Posy Fossil, a famous ballerina. And Jane, the plain, grumpy, angry, untalented, unpopular one of the trio, gets to play Mary in Bee Bee studio’s film version of The Secret Garden, and in the process learns a lot about other people and herself. This is a sunny, optimistic story which whips along at a cracking pace.

It wasn’t one of those ‘children against the grown-ups’ stories; though there were struggles and disappointments and a few crabby or difficult adults, so many helpful and interested people came into the children’s lives. And another – John and Bee, the parents, listened to their children, took their concerns seriously and let them make their own decisions. Which seemed pretty unusual for a book published in 1949. Streatfeild had lots of fun with the differences between London and Los Angeles. Manners, language, food, accents, attitudes, clothes – and from the names of characters, lots of different ethnicities. The two Black characters are Joe, a railway steward and Bella, Aunt Cora’s housekeeper. Bella is a significant character; they grow to love her, and she loves them. She becomes part of the family. The Winter family goes home happier, healthier and with lots to look forward to.

A delight.