Sometimes even murder stories or favourite children’s books don’t do the trick, and such a time is now. I have been avoiding any news about the US elections (or the war in the Middle East – and poor Ukrainians, they’re still suffering, too) but I can’t help feel the shadow of it. My feeling, in common with a lot of other people, is that Americans are stuffed if Trump wins, and stuffed if he doesn’t. Though ‘stuffed’ depends on your viewpoint, of course. And looking backwards, it’s just what’s always happened. Good and evil, an eternal struggle? The angels and the devils of human nature? As a post-war baby, a baby-boomer if you like, I grew up in a country and a world that seemed on a path of becoming fairer, more peaceful, less violently prejudiced. In a word, better. Ha! My old neighbour Margaret, who died a couple of years ago at 98, would be shaking her head right now. She saw a re-run of the 1930’s unfolding around her, and could scarcely believe that it was all happening again, re-jigged with a new cast of villains (Putin, Trump and the rest) for the 2020’s.

Sometimes even murder stories or favourite children’s books don’t do the trick, and such a time is now. I have been avoiding any news about the US elections (or the war in the Middle East – and poor Ukrainians, they’re still suffering, too) but I can’t help feel the shadow of it. My feeling, in common with a lot of other people, is that Americans are stuffed if Trump wins, and stuffed if he doesn’t. Though ‘stuffed’ depends on your viewpoint, of course. And looking backwards, it’s just what’s always happened. Good and evil, an eternal struggle? The angels and the devils of human nature? As a post-war baby, a baby-boomer if you like, I grew up in a country and a world that seemed on a path of becoming fairer, more peaceful, less violently prejudiced. In a word, better. Ha! My old neighbour Margaret, who died a couple of years ago at 98, would be shaking her head right now. She saw a re-run of the 1930’s unfolding around her, and could scarcely believe that it was all happening again, re-jigged with a new cast of villains (Putin, Trump and the rest) for the 2020’s.

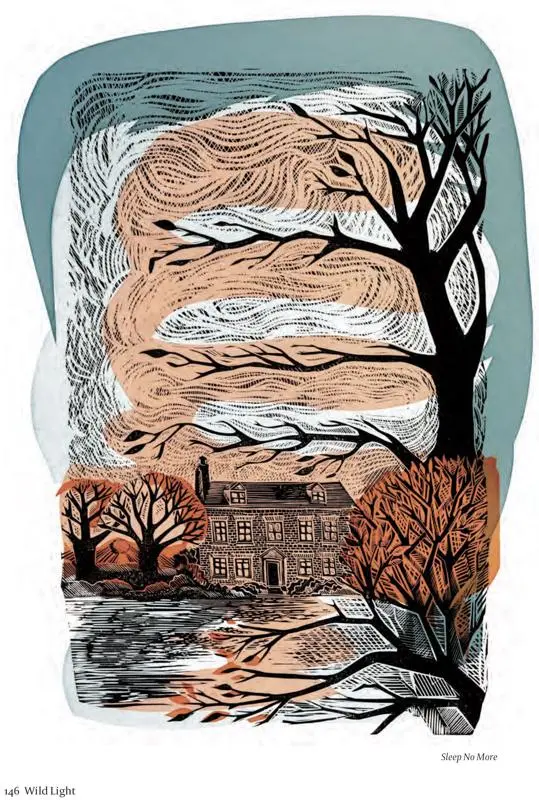

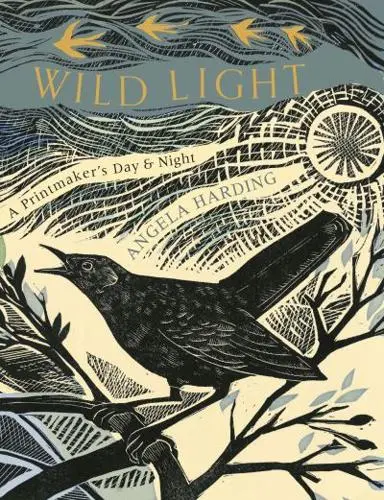

But back to the consolation of books. Books with pictures. Books of pictures! The Anglophile in me turned away in disgust for many years, and quite righteously, as I learned more and more about just how bloody awful the English were to everyone else on their many colonial adventures. However I realise that I can still love a certain kind of Englishness. And this lovely book, Wild Light: A Printmaker’s Day and Night is just SO English, harking back to the woodcuts of Thomas Bewick, an accompaniment to the poetry of John Clare and William Blake, a peek into a fantasy world of bucolic perfection.

But back to the consolation of books. Books with pictures. Books of pictures! The Anglophile in me turned away in disgust for many years, and quite righteously, as I learned more and more about just how bloody awful the English were to everyone else on their many colonial adventures. However I realise that I can still love a certain kind of Englishness. And this lovely book, Wild Light: A Printmaker’s Day and Night is just SO English, harking back to the woodcuts of Thomas Bewick, an accompaniment to the poetry of John Clare and William Blake, a peek into a fantasy world of bucolic perfection.

I haven’t gone so far as to make any actual prints yet, but I’ve been inspired to buy some lino (not the old-fashioned kind which was hell to carve, especially if it was cold; you had to put in front of a heater to warm up, and I usually ended up with a wound or two from the tools) and get out my sketchpad. I learned how to do linocuts when I did printmaking as part of my Diploma of Teaching, and over the years I’ve had phases of doing a run of them. Making linocuts is the ultimate in DIY printmaking, I think. You don’t need a lot of space, you don’t have to use chemicals or oil-based inks and most importantly, you don’t need a press. It can really be a kitchen table thing.

Harding was born in 1960, and studied art at Leicester Polytechnic and then Nottingham Trent University. She’s a prolific artist and illustrator; her kind of nostalgic ‘British countryside’ vision is having quite a moment, which is a bit ironic given that the British countryside is in deep, deep shit with so many species – like hedgehogs! – endangered. A bit like here, eh? She recently illustrated a children’s version of Isabella Tree’s book, Wilding, about the experiment at Knepp Castle. And many people would be aware of her covers for Raynor Winn’s The Salt Path, The Wild Silence and Landlines. I was toying with the idea of buying one of her calendars for 2025 – but maybe every day is a little too much of the Englishness.