I have been re-reading.

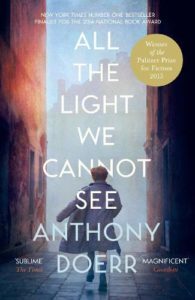

All the Light We Cannot See was the last book of the year for my Castlemaine library reading group. I read it seven or eight years ago; I was happy to read it again. It’s an epic story of World War II in Europe, told through two characters. Marie-Laure is fifteen, and blind since she was six. She lives with her father, who is employed to make and tend the locks at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Werner is a German boy who lives in an orphanage in a coal-mining area near Essen in Germany. He and his sister Jutta are close, but there’s a way out of a future in the coal mines; it’s through his technical skill and the Hitler Youth. Their separate destinies are inevitably drawn together over time and space, across Western Europe, to the French seaside town of St Malo near the end of the war.

All the Light We Cannot See was the last book of the year for my Castlemaine library reading group. I read it seven or eight years ago; I was happy to read it again. It’s an epic story of World War II in Europe, told through two characters. Marie-Laure is fifteen, and blind since she was six. She lives with her father, who is employed to make and tend the locks at the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Werner is a German boy who lives in an orphanage in a coal-mining area near Essen in Germany. He and his sister Jutta are close, but there’s a way out of a future in the coal mines; it’s through his technical skill and the Hitler Youth. Their separate destinies are inevitably drawn together over time and space, across Western Europe, to the French seaside town of St Malo near the end of the war.

The word ‘humanity’ was used a lot as we discussed the book. Perhaps we all had different meanings; or perhaps we all had the feeling that Doerr looked into the hearts of his characters, and they touched ours…though perhaps not the few utterly repulsive and evil ones. Love, kindness, decency and grace coexist with fear and cruelty. At times moving, at times harrowing, the humanity of Doerr’s gaze never falters.

We loved the way the writing carries you rapidly along. Partly it’s the immersive, sensual language and selection of detail which make the descriptions cinematic – you have the feeling of actually walking through rooms, tracing the wooden streets of Papa’s models, smelling the seawater and feeling the molluscs and anemones and seaweed. One of our readers is a bit allergic to long static passages of description, but she loved the sense of movement in this. And partly it’s the way Doerr crafts the rhythm of the chapters. Some are very short, only a page or two, and they build suspense so expertly that you’re compelled to keep reading. The changes in chapter length also added to a sense of movement.

It’s an epic story, with many characters, taking in great swathes of European history but we never felt bogged down in a lesson. Nor does Doerr beat us over the head with morality. I wished Werner would ‘do the right thing’ and support Frederick in his stand against the brutal ethos of the training school…but he did what he could, even though it wasn’t enough.

We all wanted our (by the end of the book) beloved characters to live well and prosper, or at least survive. For Werner and Marie-Laure to reconnect after the war, perhaps to fall in love; definitely for him to be reunited with his sister Jutta. For Papa to make it through the prison camp. For Frederick to recover. For everyone to live happily ever after.

But that would have been a fairytale. Instead, there were glimpses of hope, of possibility; in spite of the heartbreak, there was no tear-jerking sentimentality. A beautiful and radiant novel, a worthy recipient of the 2015 Pulitzer Prize.