I’ll start this review by admitting that Thin Places is a book I have not really read properly, but rather skimmed with the occasional comprehensive stop. I have inserted lots of paper slips to mark passages I want to re-read – but much of it I found too harrowing right now. It’s one I will perhaps read again one day, when I am not so preoccupied with the suffering of children in a world of pointless, endless adult violence and war.

I’ll start this review by admitting that Thin Places is a book I have not really read properly, but rather skimmed with the occasional comprehensive stop. I have inserted lots of paper slips to mark passages I want to re-read – but much of it I found too harrowing right now. It’s one I will perhaps read again one day, when I am not so preoccupied with the suffering of children in a world of pointless, endless adult violence and war.

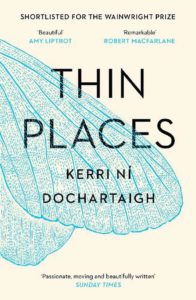

What intrigued me was the idea of ‘thin places’ (and anything Robert MacFarlane calls ‘remarkable’, I’m willing to read). Thin places in Irish tradition are those in which you feel the distance between this world and the otherworld (which can be the world of spirit, the ancestors, heaven, inspiration) shrink. We’re separated only by a veil. And the veil is thin and permeable, or it lifts; we are “held in a place between worlds, beyond experience”. Ni Dochartaigh writes beautifully of these places and how they inspire and move her.

But she also writes (beautifully too) about memory, trauma, depression and anxiety, addiction, suicidality and despair.

So, no, not uplifting. Not soothing. Easy clichés about “the healing power of nature” get a look-in; healing, or its possiblilty, is contrasted with ni Dochartaigh’s life of relentless, battering struggle.

She was born in Northern Ireland, in Derry (Londonderry, Doire) and grew up during the height of the Troubles. Her mother was Catholic, her father Protestant and in that fiercely sectarian city, her family fitted nowhere. Literally. The violence sounds terrifying. Imagine, as a five-year-old, seeing a soldier shot dead in front of you. Petrol bombs, shootings, murders, vandalism, abuse were constant. They had to shift multiple times; predictably, her family broke. Even when, in her teenage years, they found a haven in a small village, tragedy dogged her. Her best friend, a young man, was murdered.

Ni Dochartaigh leaves Ireland – she thinks, for good – to study, work and settle first in Scotland and then England, but the damage of her childhood suffuses adulthood with grief and pain. Gradually, frustratingly slowly, she circles around her childhood trauma and finds ways to heal. I confess that am slightly ashamed I skimmed so many of these pages. Just couldn’t do it. But the moments of discovery and clarity, the epiphanies, I lingered on.

Ni Dochartaigh leaves Ireland – she thinks, for good – to study, work and settle first in Scotland and then England, but the damage of her childhood suffuses adulthood with grief and pain. Gradually, frustratingly slowly, she circles around her childhood trauma and finds ways to heal. I confess that am slightly ashamed I skimmed so many of these pages. Just couldn’t do it. But the moments of discovery and clarity, the epiphanies, I lingered on.

Ni Dochartiagh is drawn to birds, moths, butterflies and winged, flying creatures of all kinds. Studying an endangered butterfly, she realises that though she’s Irish, standing on the soil of her ancestors, she doesn’t know the name for butterfly in her own language.

The loss of my ability to name both the landscape and the creatures we share it with in Irish began to sink in… I started to feel an ache, a deep sorrow, when I began to see it all in the clear light of day. How interconnected, how finely woven every single part of it all was. In Ireland, the loss we experienced has had a rippling effect on our sense of self and our place in the world, which has an impact on our ability to speak out, to protect, to name. Our history, our culture, our land, our identity: we have had so much taken away from us – we were never given any of it back.

For the first time properly in a long time, I felt the loss of things, of precious things – the loss of things I realised I could not name.

I wonder whether some of Ni Dochartaigh’s thoughts and feelings would be understood or shared by Aboriginal people. On my recent travels in Central Australia, standing in awe-inspiring places like Standley Chasm, Ellery Big Hole and Ormiston Gorge, I knew these were not their real names. And I knew I did not understand or feel what the rocks and water were, what they meant. As a friend recently said to me, we (Anglo-Celtic-Australians) can ‘read’ the landscape of somewhere like Yorkshire or Cornwall better than we can read our own. And the central desert country, so austerely beautiful, is just not in our DNA.

Ni Dochartaigh writes of the Celts, ‘…almost everything in the natural world was tied in some way to the greater being – the spirit – of the earth. For our ancestors, our role in it all as guardians was one of unshakeable magnitude’.

I have a tendency to think of nature, the natural world, as somewhere beautiful and calm that you go into, like a garden, or somewhere remote or wild you have to travel to. I loved Ni Dochartaigh’s discovery of the small wildnesses of an urban environment.

I have a tendency to think of nature, the natural world, as somewhere beautiful and calm that you go into, like a garden, or somewhere remote or wild you have to travel to. I loved Ni Dochartaigh’s discovery of the small wildnesses of an urban environment.

I took my anxious body a different path. I made my way around the football pitch instead of along the stream, up a hill with empty energy drink cans and one discarded stiletto into a wee copse. Burnt grass and shards of glass from Tesco own-brand vodka bottles, no light to be found at all. And then she came, wild and beautiful, in flight in the least likely of settings – a mottled brown and white moth. I followed her path above broken glass bottles – things that speak of the addiction and poverty… Later, before the night fell, I looked her up and found that she was an Oak Beauty. She is very specific to woodland in this wooded, broken city of mine. Even as I thought I was open of mind and eye, the moth that afternoon told me to come closer still, tells me – even now – that all is not lost in this place, not yet.

I have always enjoyed looking out of the window of a train. Even as a little kid, I was fascinated by back yards, the rear views of buildings and especially the weedy edgelands along the tracks. Last year, on my way to a particularly upsetting funeral, I occupied myself by noting the names of the plants I recognised. Ivy, periwinkle, nasturtium, geranium, arum lily, cotoneaster… In that way, I came back to myself, and was able (I hope) to be of some use to the bereaved daughter. Are those neglected margins of unwanted wild growth thin places? I’ll give it some thought.