Some time in the early 1990’s, in an Op Shop or a second-hand bookshop, I picked up a book called Turn: The Journal of an Artist by Anne Truitt. I had no idea at the time who Anne Truitt was. It was before the Internet – imagine that! – and perhaps I wasn’t curious. I don’t remember much about the book itself. At some point, in one of my regular purges, I gave it away. But I must have thought it valuable enough to copy out this passage:

In the Cluny Museum yesterday, I stood astounded among the sculptured faces of people who had left behind them evidence that their vital efforts in the 13th century had not been in vain because they spoke to me of comfort.

The faces of people who had struggled as hard as they could to be good, and who had, at last, to accept their own humanity, not as a fatal limitation, but as an available form of nobility. They gave me to understand that the effort of a human life can only be this acceptance, a submission to limitations that admit, include, the human virtues as worthy of proportionate divine recognition.

I have made a mistake in not paying proper attention to the story of human history. The Cluny faces report to us that be be human can be what, after all, God expects from us.

I think this must have struck a chord with me because for a long time, and probably since I was a child, I have been aware that set beside the pinnacle achievements, the heroic big stuff – battlefields and podiums, medals and glittering prizes – is ordinary, small-scale, day-to-day heroism. Or to use Truitt’s word, ‘nobility’.

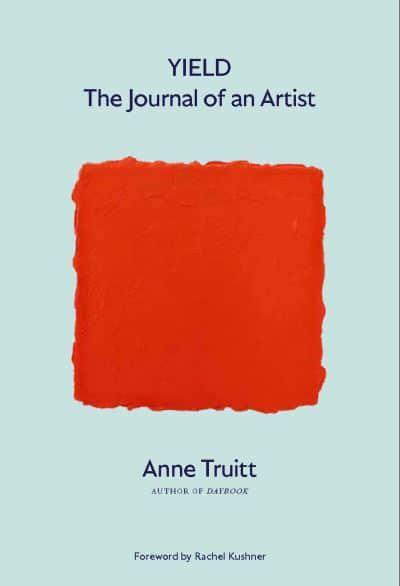

A couple of weeks ago my brother offered me a pile of books to borrow. Novels, mainly crime, and the recently published journal Yield by Anne Truitt.

A couple of weeks ago my brother offered me a pile of books to borrow. Novels, mainly crime, and the recently published journal Yield by Anne Truitt.

I’ve been enjoying journals and memoirs this year – my May Sarton binge comes to mind – so I took Yield and found an artist, in her final years (Truitt died in 2004; this is a previously unpublished part of her archive), reflecting on her life and work. Life as a woman, and a woman artist, a sculptor; the constant of her creative work, which becomes more difficult with age.

How to describe it? Spare, searching, wise, honest, human.

And I remembered the paragraphs about the Cluny faces I’d copied in a book all those years ago, and I Googled Anne Truitt’s work, and the Cluny museum, and I borrowed all the Truitt journals. I’m nearly at the end of Daybook (1982), the first. It’s galvanised me (that’s a classier way of saying it’s provided a necessary kick up the arse) to think more deeply about my current writing projects, about what I hope to accomplish, and why.

And about the temptation – because writing takes such a long, long time – to take the easier or easiest path.

She wrote that artists:

She wrote that artists:

…catapult themselves wholly, without holding back one bit, into a course of action without having any idea where they will end up. When they find that they have ridden and ridden – maybe for years, full tilt – in what is for them a mistaken direction, they must unearth within themselves some readiness to turn direction and to gallop off again.

With a sinking heart I recognise that mistaken direction. Actually, I’d already recognised it, I simply hadn’t admitted it to myself. So here we go again. Here it is. To quote Anne Truitt, it’s this:

…the strict discipline of forcing oneself to work steadfastly along the nerve of one’s own intimate sensitivity.

Ouch.