The NHS gives the official definition of carer as ‘anyone, including children and adults, who looks after a family member, partner or friend who needs help because of their illness, frailty, disability, a mental health problem or an addiction and cannot cope without their support. The care they give is unpaid.

The NHS gives the official definition of carer as ‘anyone, including children and adults, who looks after a family member, partner or friend who needs help because of their illness, frailty, disability, a mental health problem or an addiction and cannot cope without their support. The care they give is unpaid.

All the same, it’s a tricky word. It’s a noun freighted with meaning and requiring qualification. It brings with it a hint of transaction, of an inequality, which is all the more uncomfortable if the person you’re caring for is someone you love. By using it, however accurate it might be in terms of the day-to-day realities, there’s a risk that it redefines a partnership, a balanced give-and-take relationship, and turns it into an obligation; carer and patient, carer and client. One is active, the other passive, whereas every carer knows there’s nearly always come kind of reciprocity even in the darkest hours.

You are still you, and they are still they.

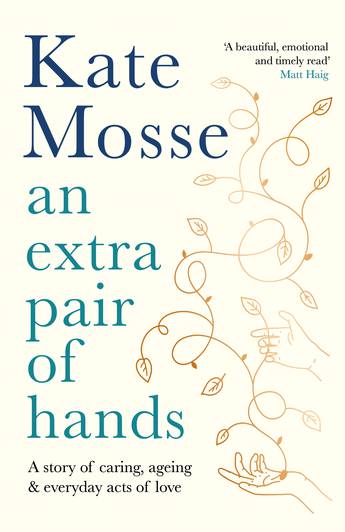

An Extra Pair of Hands by Kate Mosse

Profile Books/the Wellcome Collection, London, 1921

My sister-in-law gave me An Extra Pair of Hands by Kate Mosse for Christmas. Subtitled A story of caring, ageing and everyday acts of love, it’s a memoir interspersed with reflections on the ‘invisible army of carers holding families together’.

I think she gave it to me because it echoed my own experience, and because of my recent stint of working in the aged care sector. Mosse, a best-selling novelist (the Languedoc series), non-fiction writer and playwright, describes caring for her parents Richard and Barbara. She helped her mother care for her father as he declined with Parkinson’s Disease, and then supported her when she was widowed.

Mosse and her husband had a large house in Chichester, in Sussex; her parents came to live with them. This is what we did too, though in reverse. My husband and I, with our 18-month-old son, moved in with my parents in 1998. Dad had Parkinson’s, like Mosse’s father, and also cancer. After he died in 2002 (it was the 20th anniversary of his death on the 5th January) we cared for my mother until she died in 2008. Ten years; all of my 40’s.

Not only Mosse’s parents, but also her mother-in-law Rosie joined the family. Rosie sounds like a force of nature; unstoppable, vivacious, life-enhancing. Plenty of Blitz spirit there. Rosie and Barbara, two very different women, even forged an unlikely but close friendship after Barbara was widowed. I enjoyed Mosse’s descriptions of their outings, their travels, their conversations. Importantly, as well as detailing the crises and difficulties of care, she celebrates the joys and pleasures of being with older people.

Mosse talks about guilt, tiredness and boredom, about juggling priorities, about the struggles of navigating the health system and managing in the times of covid. But this is not an incisive or challenging book. It doesn’t set out to be. It’s gentle in scope. Mosse says explicitly that she did not choose to write about anything too personal. The book has a slightly sanitised feel to it; there is no bum-wiping here, but neither could there be. Suffusing her story with love and respect, Mosse preserves their dignity. If I wrote about my parents, I suspect it would be much the same.

She wants the reader to think about ageing not as something that happens to generic old people, but to real people, loved people, with histories and personalities and gifts still to give. It happens to families. As the jacket blurb says,”…most of all, it’s a story about love.”

I had ten years as a carer for my parents.

My experience with strangers, as a home and community carer, was brief. Three months, if you count my placement. I got sick, I had to have some time off, and now I am unsure about going back to it. I might be too old.

It was intense, physically and emotionally. You go into people’s homes and you see, intimately, up close and personal, how they live. They are completely vulnerable – literally. They are naked as you help them to shower and dress.

Bodies. Skin. What a surprise; under the old-lady nighties can be beautiful old bodies, sturdy and strong with gorgeous folds and curves (the clients were mainly women, only a few men). Maybe it’s my early years at art school, my life-drawing class; I thought they’d be wonderful to sketch. “You never saw much sun,” I commented to one lady with perfect skin, but, “Oh no,” she said, and reminisced about her first bikini at fifteen. Her father was outraged but her mother over-ruled him. She came home from the pool lobster-red. “I told you so.”

But ageing is not always pretty. You see tissue-thin skin that’s breaking down, ulcerated, bandaged, inflamed; occasionally you have to try to keep hands, arms or feet dry with plastic bags and tape. You see arthritic deformities, bones sticking out with emaciation, protruding swollen joints, scars and wounds.

Or obesity. Even morbid obesity. Incontinence. Smells. I’m not on some higher plane, I noticed these things, observed them, was moved by them. Does this sound like lack of respect? I don’t mean it to. Before I did my placement, I was worried that I’d feel disgust, that I’d react, even (beyond my control) retch. But finally, when I was there and performing intimate care for people, it was just so human. It was fine. It felt like a privilege. I mean that.

You see the pain and effort of living in an old body. Moving in and out of baths and showers takes time. There’s courage and endurance and willpower involved. I met with good humour, no humour, profound grumpiness. No judgement. I think my lecturers taught me well, or perhaps I worked it out for myself. This is who they are, where they are; you do what you can. You do it for lovely, kind, welcoming people who reward you with smiles and thanks, and others who are not lovely, who are withdrawn into pain and despair. You are there also for the carers, the spouses or family members. Sometimes there was a cup of tea or a chat, and sometimes not. You see loneliness, frustration, embarrassment, exhaustion. You see love.

In the end, it’s just so human.

I’m going to pass An Extra Pair of Hands on to a friend my age, a daughter who is caring for her 97-year-old mother. Though there is little on the nitty-gritty of care, Mosse depicts the conflicting emotions of carers so well. The relief and yet the grief and profound sense of loss when the role ends. I think it will help my friend feel validated, and understood.

Beautiful post Susan. I hope you do go back to home care. The community needs compassionate people like you caring for the vulnerable. You are so right, it is a privilege.

And the stories to be told, if someone will listen.

Thank you so much for that comment, I really appreciate your taking the time. I think your last words – “if someone will listen” – hold the key.

So many of us don’t want to listen. Ageing is scary or challenging because it means loss. And people in extreme old age – over 90 – are so often vulnerable, dependent, unwell, infirm, frail… It could be as simple as ‘reminds us of our own mortality’, and we don’t want to think about it. But there’s also the uncomfortable guilty knowledge that we, the people, through successive governments, don’t care enough (to be blunt) to spend the requisite amount of money on the sector.