The Ouse is a small English river, only 84 kilometres long (and for comparison, the Thames is 346 kilometres and here in Australia, the Murray is 2,508 kilometres long). To those who are interested in literary lives, it is most famous as the river into which Virginia Woolf waded, with stones in the pocket of her coat, and drowned. One midsummer day in 2009, in the aftermath of losing her job and her relationship with the man she loved, Olivia Laing set out to walk the length of the Ouse.

The Ouse is a small English river, only 84 kilometres long (and for comparison, the Thames is 346 kilometres and here in Australia, the Murray is 2,508 kilometres long). To those who are interested in literary lives, it is most famous as the river into which Virginia Woolf waded, with stones in the pocket of her coat, and drowned. One midsummer day in 2009, in the aftermath of losing her job and her relationship with the man she loved, Olivia Laing set out to walk the length of the Ouse.

I wanted to clear out, in all senses of the phrase, and I felt somewhere deep inside me that the river was where I needed to be. I began to buy maps compulsively, though I’ve always been map-shy. Some I pinned on my wall; one, a geological chart of the underlying ground, was so beautiful I kept it by my bed. What I had in mind was a survey or sounding, a way of catching and logging what a little patch of England looked like one midsummer week at the beginning of the twenty-first century. That’s what I told people, anyway. The truth was less easy to explain. I wanted somehow to get beneath the surface of the daily world, as a sleeper shrugs off the ordinary air and crests towards dreams.

So, here is another woman walking, along a meandering path beside the Ouse, from its rising-place in a muddy paddock to its exit at the coast. There is nothing spectacular in this journey, no sublime landscapes or scary wild creatures or blizzards or floods. She doesn’t sleep rough – she spends her nights sleeping at inns along the way, or in the houses of friends – and nothing is more gruelling, really, than the occasional hot day. But that’s not the point; Laing hasn’t set out to challenge herself to feats of physical endurance; she is walking and thinking and feeling and looking and – I imagine – writing, if only in her head.

And the writing is the thing. Poetic, attentive, hypnotic in its accumulation of detail.

It was just after sunset and everything had stilled, the sky shot faintly with rose. The reflections in the lake seemed sunk very deep. The water pleated as carp sank and climbed, occasionally breaking the water as shivers. Beneath them, the clouds made their way east. At the far side of the lake the trees were reflected in sooty green and when the fish jumped there the ripples ran in white concentric circles. On the near side, where there was only pale sky on the skin of the water, the ripples flashed dark, a trick of the light I’d never seen before.

Her sensitivity to landscape, to the details of birds and plants and animals that inhabit the landscape, make this a slow and meditative summer journey, with the writing and the structure of the book as meandering as its subject. Subjects, plural. For Laing weaves in all sorts of topics; biography, literature, mythology, science, history. Neolithic settlers, Saxon villages, Norman castles, Tudor sewage works; farmers and fossil-hunters and medieval soldiery. Other writers apart from Woolf make an appearance on her journey. There’s Kenneth Grahame, author of The Wind in the Willows, and Iris Murdoch.

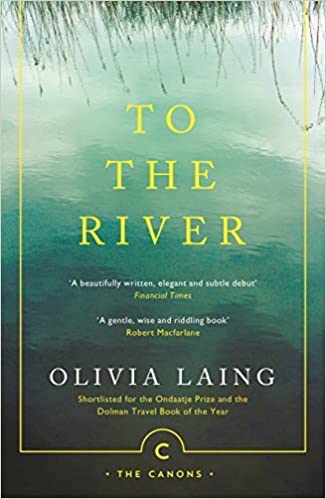

A book like this is probably not for every reader, but then what book is? It doesn’t fit neatly into a category (memoir? biography? nature?); it’s not a self-help book exhorting us to get out into nature, nor is it inspirational (challenges overcome!) or spill-your guts confessional. I’m not really sure what it is. Beautiful, I suppose.

I love these sorts of books that spill over into several categories; it can be like watching someone’s thoughts turn over and simultaneously seeing through their eyes. It can be such an intimate experience.

I wonder if Patrick Leigh Fermor was the pioneer in this kind of travel/nature/ journey writing? (I’ve just finished A Time of Gifts.)