I couldn’t see myself as one of those women – I thought that eating disorders only happen to women who are vain and selfish, shallow and somehow stupid: it took me years to realise that the very opposite is true, that these diseases affect people, men and women both, who think too much and feel too keenly, who give too much of themselves to other people. I knew I wasn’t vain, I wasn’t selfish; but I have always felt vaguely, indeterminately sad, too vulnerable to being hurt, too empathetic and too open, too demanding and determined in the standards that I set for myself and my life.

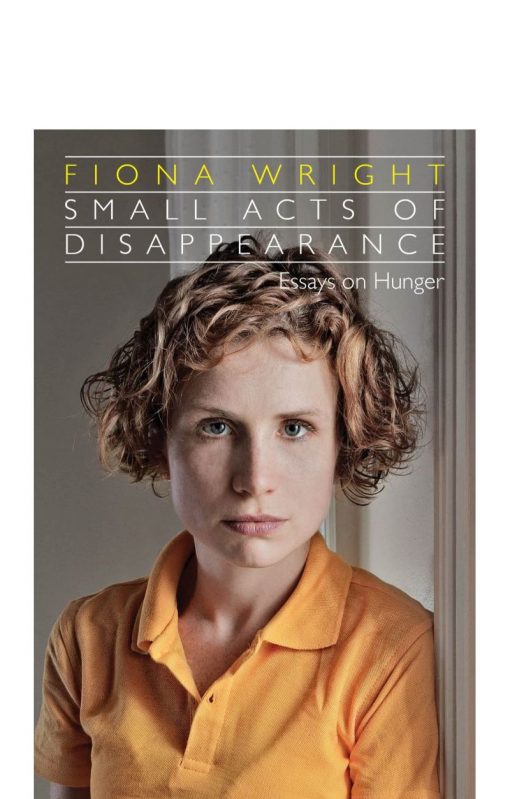

from Small Acts of Disappearance: Essays on Hunger by Fiona Wright; Giramondo, Sydney 2015.

I’m a bit squeamish about the memoir genre. Sometimes I feel a bit voyeuristic. Sometimes I wonder what the writer’s family or lovers or friends think about reading themselves on the page.

Sometimes, too, I wonder how people can bear for strangers to know so much about them. I wonder what this says about me.

It’s the exposure, I guess. Exposing the raw and ugly, the painful, the bodily and sexual and intimate. I don’t think it’s just inhibition (thought that’s possibly part of it). I genuinely feel queasy about readers – strangers – knowing very much about me, to the extent I’m even torn about the adult novel that’s currently in the works. In some ways I don’t actually want anyone to know the kinds of things I think about. But I want to write, I want to be published, and I want to be read – so that’s pretty silly, eh? I’ll get over it. And I know that one can understand writing about the deeply personal as a ‘taking back’ of power. You’re saying no to shame, to hiding and concealing, to feeling bad about who you are. Therapy, in a particularly public form? Maybe, but a young woman in my town has just published a zine about her recovery from chronic fatigue and depression; not only was I was moved by her courage in revealing her struggle, but by her hope that her story will help others in a similar situation.

Fiona Wright is a poet and critic. Her book of essays offers (as the back-cover blurb says) a number of different perspectives on her disease as well as the more straight-forward memoir sections. I enjoyed the literary, philosophical and historical diversions. But it was the personal that got to me. And because Wright is a poet, she can describe her illness in beautiful precise language, intense with detail, description, metaphor.

It’s background noise. A CD jammed on a track. A frog in a pot. A cork in a bottle. A secret world. A safety net. A parasite, a function, a friend.

But I confess that I too was guilty of thinking that an anorexic was one of those women, and after reading her book I feel sad, somewhat guilty, and full of fellow feeling. So many people (me included) have suffered, or are made to suffer – like Wright – for their vulnerability. So many people feel that it’s their own fault. They blame themselves, perhaps – thinking I’m too thin skinned, or not robust enough, or too sensitive, or weak, cowardly and pathetic. And it shows up in some way. Not necessarily as anorexia – me, I like food much too much not to eat – but in some form of self-hatred or self-punishment or self-control. Depression or anxiety or just a low-level scourging of self for failure of some kind.

Is there a happy ending? Not so much. Recovery is a work in progress. The last words of the last essay are about walking through the grounds of her old university. the carillon bells are playing, and when she stops to listen, she’s overcome by a deep sadness for her past self, alone, lost and confused. Sadness for ‘the girl who had this hunger already within her, and for the woman who I’ve been, who I’ve become.’