Since in Ashdod everybody always ended up on the beach, in order to maintain my friendships I felt I needed to make an occasional appearance there. I’d the wait on the sand… for everyone to return from their swims, glistening with water and joy. Oh, how I yearned to join in…

Since in Ashdod everybody always ended up on the beach, in order to maintain my friendships I felt I needed to make an occasional appearance there. I’d the wait on the sand… for everyone to return from their swims, glistening with water and joy. Oh, how I yearned to join in…

Despite my sense of acceptance by my new friends, I still wouldn’t disclose my scars, so intense was my fear of disappointing, and witnessing that disappointment. And I feared pity. This anxiety hasn’t faded over the years. No matter what I’ve achieved since, how much love has come my way or how many books on feminism I’ve read, I still feel ashamed about my scars as if they’re some sin I’ve committed. I’ve just learned to cover up this anxiety with giant smiles the way I cover my body.

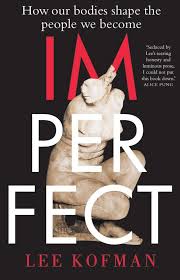

Lee Koffman spent her early years in Russia. Her congenital heart defect needed multiple surgeries, and even though her parents paid not to have the surgeon known as ‘the butcher’ operate, nevertheless little Lee was left with massive scarring on her chest. At least she survived. And she was well.

Until she was hit by a bus, nearly lost her leg and ended up with yet more severe scarring. Soviet medicine was strictly utilitarian; no cosmetic surgery. As a little kid, the scars didn’t bother her so much, but as a teenager, moving to Israel (and later, Australia) she encountered a hot climate, beach culture and the cult of the ‘body beautiful’. Hiding her scars became an obsession.

Awareness of these imperfections continued into adulthood, through her success in academia and as a writer, through relationships, a couple of marriages and motherhood. This book is part memoir and part investigation into the ways our appearance – or Body Surface, as Kofman calls it – shape us and the ways in which other people regard us. She talks to people with scarring from accidents and burns, people born with dwarfism, albinism and other congenital health issues, obese people, people who are into extreme body modification. She looks into the world of fetishists; people (almost always men) she calls ‘Wabi Sabi lovers’ who are only turned on by very large women, or amputees, or women with scars; and the world of high fashion, where the ‘new rules of beauty’ see models with conditions such as albinism and ‘cat-eye’ syndrome, as well as amputations, on the catwalk and in magazines. At the end of the book, she turns back to herself, and talks about how she’s emerged as both resilient AND messed-up on account of her scars.

And how shall I end my story? I used to fantasise that writing this book would become my Ultimate Healing Act. Yet now that I’ve finished it, I still haven’t found an epiphany or a grand redemption. Mine, then, isn’t the popular ‘I’ve been through hardships and now I resolved them all’ narrative…

Imperfect was our library book group selection for this month. Some – me included – found it interesting enough to to want to finish and discuss; it opened our eyes to the disastrous shortcomings of the Soviet medical system, youth culture in Israel and the desires of sexual fetishists out there seeking all kinds of ‘imperfect’ bodies.

A few of us had sympathy or compassion for Lee Kofman, but others thought she was narcissistic, shallow and irritating and so gave up on the book.

And one member couldn’t even bring himself to start reading. So, all in all, a successful choice!

This may sound paradoxical, but I believe that until we stop saying that beauty, or appearance really, is ‘skin-deep’, until we concede how much it matters, we cannot make it matter less. To change private lives and public attitudes, the conversation about Body Surface must first be honest, move beyond cliches and politeness, make space for any genuine feelings – be these joie de vivre or frustration and grief. And yet in another paradox, the lower our expectations might be to always love and always accept our appearance as it is, the better chance I think we stand of healing the psychic wounds Body Surface may generate.