William Mayne is one of the cohort of writers who formed the ‘second golden age’ of British children’s books. From the late 1950’s to the 1970s, writers like Rosemary Sutcliff, Alan Garner, Phillipa Pearce, L M Boston and Joan Aiken produced future classics. They were the books that I read avidly. Yet I can’t think of any of Mayne’s more than 100 books that I actually read when I was a kid.

William Mayne is one of the cohort of writers who formed the ‘second golden age’ of British children’s books. From the late 1950’s to the 1970s, writers like Rosemary Sutcliff, Alan Garner, Phillipa Pearce, L M Boston and Joan Aiken produced future classics. They were the books that I read avidly. Yet I can’t think of any of Mayne’s more than 100 books that I actually read when I was a kid.

Now I’ve finished Earthfasts, I think I know why. It’s his style. It’s hard to describe, but the best I can do is ‘spiky’. You think you’ve got a grip on it, and then you get snagged on a sentence or even a single word.

Darkness began to lie more heavily now. In a gap in the cloud overhead a star looked out, then drew the curtains on itself and went back to its empyrean concerns. The drummer boy was still solidly there, but he was less easy to see. Keith looked at David, and David was less easy to see as well, so that the drummer boy was not unnaturally fading as he had unnaturally come…

It’s not easy to read; Mayne makes you work. It’s challenging. There is a lot of description.

‘Empyrean concerns’? I had to look it up. And I don’t understand the last sentence. Which is OK, and as an adult reader I can cope – however reluctantly, because I’m a lazy reader – with challenge. So I persevered.

Keith and David, who seem to be around 13 or 14, are both unusual boys, serious, intense and intelligent. It’s a midsummer evening, and they’re on the outskirts of their rural Yorkshire town when they hear what sounds like drumming coming from under the ground. They see a mound of grass move and change shape – and out of the hill comes a boy from another time. He’s a drummer boy called Nellie Jack John who went into an underground tunnel 200 years ago to find King Arthur’s treasure. I won’t give any spoilers, but there are giants, an heirloom boggart, wild pigs, and a candle with a mysterious, addictive, un-extinguishable flame. The two boys, both science-minded, try to make logical sense of events. Detective work brings them a number of clues from the past. There are episodes of fast moving adventure and even some humour. However a nightmare-prone child might be advised not to read it until they’re older; by the last of the four parts, the story has turned dark, scary and sometimes disturbing.

Some of my very favourite things are here – time slips, supernatural events, myths and legends that seep into everyday life, ancient rural landscapes, the peculiar, stratified social world of post-war Britain – and I certainly kept turning the pages. I recognised the quality and originality, the beauty of some of the writing, the intensity Mayne brought to the characters of Keith and David and above all the genuinely weird character of the events unleashed when the drummer walked out of the hillside. Really, there was a lot to like about Earthfasts… but I didn’t love it. And I’m not sure what a child reader would make of it today. According to some of the articles I read, Mayne’s books were never widely popular among children. In fact, they were more popular with adults.

However, I still thought I’d like to find some more Mayne to read.

But maybe I will have trouble finding more books. They were apparently quietly removed from many British library collections in 2004 after he was convicted of 11 counts of indecent assault against little girls. He spent a couple of years in prison and was placed on the sex offenders register for life. (He died in 2010.) It would be difficult to reissue the books of a convicted pedophile, even if he is a neglected master.

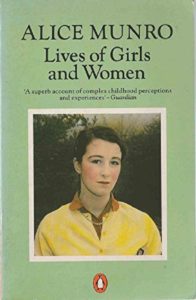

I recently found out about the famous Canadian writer and Nobel Prize winner Alice Munro. Munro stayed with her second husband after he not only pleaded guilty to sexually abusing her daughter, but described the 9-year-old girl as a seductress and home-wrecker. She downplayed the nature of the offences, used her fame and reputation to quash publicity, and effectively chose her husband over her child.

I feel so sad! Munro’s Lives and Girls and Women is one of the touchstone books of my early adulthood. I learned not to feel inferior because my literary aspirations weren’t heroic. I learned that short stories about seemingly ordinary and quiet lives – female lives, interior lives – can outshine the Big Male Novel. I read and re-read her books, buying each new one when they came out. I learned so much, not just about writing and language, but about womanhood. I don’t want to lose any of that, but…

I feel so sad! Munro’s Lives and Girls and Women is one of the touchstone books of my early adulthood. I learned not to feel inferior because my literary aspirations weren’t heroic. I learned that short stories about seemingly ordinary and quiet lives – female lives, interior lives – can outshine the Big Male Novel. I read and re-read her books, buying each new one when they came out. I learned so much, not just about writing and language, but about womanhood. I don’t want to lose any of that, but…

It’s a whole other big question, isn’t it? What to do, how to think, about writers like Mayne and Munro, whose private lives reveal such flaws? I’m afraid I don’t have any answers.

I remember reading Earthfasts in maybe grade 5 or 6 and feeling unsettled by it — I didn’t love it. And then as an adult finding out about William Mayne’s history and shying away. However apparently he wrote some books about a boys’ choir which I would be interested in checking out, I’ve never come across them, maybe they all went in the skip.

I haven’t read any of Alice Munro’s work and now I feel this news will hang too heavily over it for me to read it objectively. If there is any such thing.

I think you have to separate the texts from the author. Sometimes, of course, books can be sexist or racist, and can be discarded or critiqued. Mayne’s books however aren’t condoning abuse or harassment in any shape or form. You can find most of them secondhand and cheap online.