Begin at the beginning, go to the end, and there stop – that’s what Rickie, our English master, told me when it was settled that I should write the story. It sounds simple enough. But what was the beginning? Haven’t you ever wondered where things start? I mean, take my story. Suppose I say it all began when Nick broke the classroom window with his football. Well, OK, but he couldn’t have kicked the ball through the window if we hadn’t just got super-heated by winning the battle against Toppy’s company. And that wouldn’t have happened if Toppy and Ted hadn’t invented their war game, a month before. And I suppose they’d not have invented their war game, with tanks and tommy guns and ambushes, if there hadn’t been a real war and a stray bomb hadn’t fallen in the middle of Otterbury and made just the right sort of place – a mass of rubble, pipes, rafters, old junk, etc. – for playing this particular game. The place is called ‘The Incident,’ by the way. But then you go back further still and say there wouldn’t have been a real war if Hitler hadn’t come to power. And so on and so on, back into the mists of time. So where does any story begin?

Begin at the beginning, go to the end, and there stop – that’s what Rickie, our English master, told me when it was settled that I should write the story. It sounds simple enough. But what was the beginning? Haven’t you ever wondered where things start? I mean, take my story. Suppose I say it all began when Nick broke the classroom window with his football. Well, OK, but he couldn’t have kicked the ball through the window if we hadn’t just got super-heated by winning the battle against Toppy’s company. And that wouldn’t have happened if Toppy and Ted hadn’t invented their war game, a month before. And I suppose they’d not have invented their war game, with tanks and tommy guns and ambushes, if there hadn’t been a real war and a stray bomb hadn’t fallen in the middle of Otterbury and made just the right sort of place – a mass of rubble, pipes, rafters, old junk, etc. – for playing this particular game. The place is called ‘The Incident,’ by the way. But then you go back further still and say there wouldn’t have been a real war if Hitler hadn’t come to power. And so on and so on, back into the mists of time. So where does any story begin?

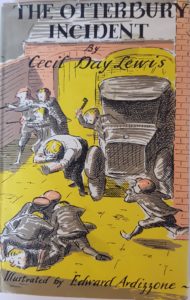

Well, when it comes to children’s fiction from the late 1940s to the 1960s, the boys certainly did get more excitement and action. The Otterbury Incident was a wild ride from page one. The narrator, George – not quite fourteen – sets the scene (above), and foreshadows some of the characters (Johnny Sharp and the Wart, Inspector Brook) and mentions a gang of crooks. Then it’s on. The exciting imaginary battles flip into imaginative fund-raising for poor Nick who broke the window. The two companies make peace and combine in Operation Glazier to raise five pounds to repair the window. This is so that Nick, orphaned during the Blitz and living with a violent guardian, doesn’t get beaten (again) and have his puppy sold. The money is too much of a temptation for the obnoxious spiv Johnny Sharp, who with his minion the Wart, steals the funds. How the kids investigate the crime and punish the perpetrators is riveting. I loved the first-person narration; George was a smart, funny, quick-witted boy, not always brave, and on occasion self-doubting. I read the book in one go. A couple of unfortunate racist and anti-Semitic phrases stuck out in a book that would be otherwise a perfectly readable WWII-era children’s adventure in 2024.

And by the way, C Day Lewis is not to be confused with C S Lewis. C Day Lewis (1904-1972) only wrote a couple of children’s books. He was more famous as a poet; in fact, he was Poet Laureate of the UK from 1968 until his death in 1972. He also wrote highly successful detective novels under the name Nicholas Blake. It sounds like he had a busy but disorderly private life – is that typical of poets? – juggling marriages and mistresses with his literary and academic work. The actor Daniel Day-Lewis is one of his children.

And one more thing…

And one more thing…

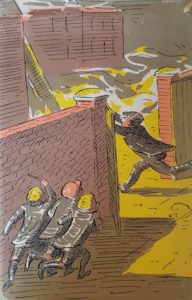

Like a lot of books that I love from this era, it was beautifully illustrated, by a top illustrator. There are 23 small black and white pictures places throughout the text. They match the writing – there’s such an impression of activity and speed. Edward Ardizzone (1900-1979) was, in his day, one of the most famous British illustrators, as well as being a war artist, designer and commercial artist, with an instantly recognisable loose, slightly cartoonish style. As a child, I loved his dreamy, poetic illustrations for a collection by Walter de la Mare called Peacock Pie. Wikipedia tells me that he wrote and illustrated over 20 of his own books, and did the pictures for dozens more.