Spring came in with sunshine and warmth. Yesterday in the late afternoon I stood with my husband in the courtyard at the front of our house. A grey shrike thrush flew to a blossoming plum tree, perched on the crown for all to see and sang his little heart out. We watched, thrilled, as his throat and chest vibrated with the effort; according to my bird book, The Australian Bird Guide by Peter Menkhorst et al, this little grey bird has a pure, ringing, rhythmic voice, and a liquid five-note song. All that, and more; his voice is audible joy. After broadcasting to the neighbourhood, he rushed around from bush to shrub, perching to flirt and pose and add a note or two, quite un-shy and seeming actually happy to be in our presence. Eventually we heard an answering bird – just a short, sharp single note, which the book describes as a ‘contact call’ – and our thrush flew away.

We were out there to survey the results of my recent planting spree – violas, pink and purple and yellow; a germander bush, silvery leaved with pale lavender flowers; two different heucheras (lime green and deep purple), low and sprawling, which I hope will want to become ground covers; a hellebore or winter rose, with palest green flowers; and two plants I’ve never grown before, bought to see how they turn out, a penstemon, dark green strappy leaves and blue flowers; and a saxifrage, which looks like a tiny squashed cabbage and is supposed to erupt with little pink flowers on stems. We shall see.

That’s the great thing about gardening; you wait, and then you see.

That’s the great thing about gardening; you wait, and then you see.

We were seeing how unpromising looking bulbs turn into absolute stunners. My little crocus (crocuses? crocii?) are nearly finished but now it’s time for the big guns; tulips. They are trembling on the brink. After going for the deep reds, purples and nearly-blacks in the past, with a not-to-be-repeated diversion into frilly weird pinkness last year, I have gone for orange and ginger this time. Stupidly, I put the tags in the pots but they were made of card and so I have no idea what my beauties are. But it doesn’t matter. I know that some gardeners are systematic about such things, so that they can repeat a success and avoid a failure, but somehow I am trusting that next year when I’m looking at the bulb catalogue, I’ll remember. And maybe, anyway, I will choose another colour.

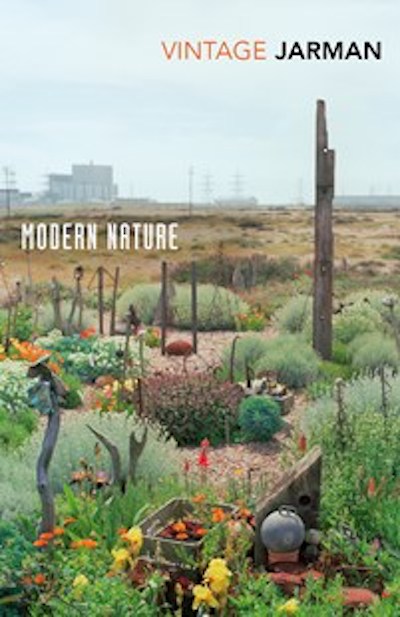

My last post was inspired by the traffic essay of Rachel Cusk; this one, by reading Derek Jarman’s diaries from 1989-90, Modern Nature. The book is a nice, cheap Vintage reprint with an introductory essay by Olivia Laing, who is my new girl crush. I’m not sure that many young people would know who Jarman was; he died of AIDS-related illness in 1990. He was a writer and gay activist, an artist, stage designer and perhaps most famously, a film director. As a young art student in the late 1970’s, I went to see his angry, sad, violent Jubilee. I remember not liking it, but then I didn’t ‘get’ punk. I was more David Bowie than the Sex Pistols. What I have never forgotten was his spellbinding version of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. The final sequence, where a crew of uniformed sailors dance and jazz singer Elisabeth Welch sings ‘Stormy Weather’ is utterly magical.

And he was a gardener. At Prospect Cottage, his retreat on the beach at Dungeness in the shadow of the nuclear power station, the odds were stacked against him. Wind, exposure, salt, shingle and stones and sand for soil – nevertheless, he persisted.

Modern Nature takes in all of these strands. Sometimes the contrast is jarring. He makes lists of plant names that sound like incantations – loosestrife, bugloss, buckthorn – and then, back to London, goes cruising on Hampstead Heath. This:

There is the suspicion of rain in the air, but a dry wind blows. The downy seeds of the willow herb float by. The back seed pods of the broom split with a crackling sound.

At the end of the garden the sloes are turning purple, and the blackberries are ripe. My wild pear tree wilts in the drought, and the nettles are dead and rattle in the wind.

And this:

Finding sexual partners was difficult and they were often transitory – hardly bothered to take their pants down before buttoning up. And the police might raid, send the prettiest ones in as agents provocateurs. They had hard-ons but didn’t come. Just arrested you.

But now, halfway through the book, I’m loving the juxtaposition. Olivia Laing says in her introduction that her adult life was founded in the pages of this book.

It was here I developed a sense of what it meant to be an artist, to be political, even how to plant a garden (playfully, stubbornly, ignoring boundaries, collaborating freely).

Ignoring boundaries. Exactly. It’s what he does here. I guess that’s the beauty of the diary form. You can recount your daily life, you can reminisce and gossip. You can talk to yourself about sex and death (in those far-off days, being diagnosed as HIV-positive usually was a death sentence) and art and memory. And you can name the plants that you nurture and grow – wild fig, sempervivum, dead-nettle, night-scented stock – as you submit yourself to the eternal rhythm of the seasons.