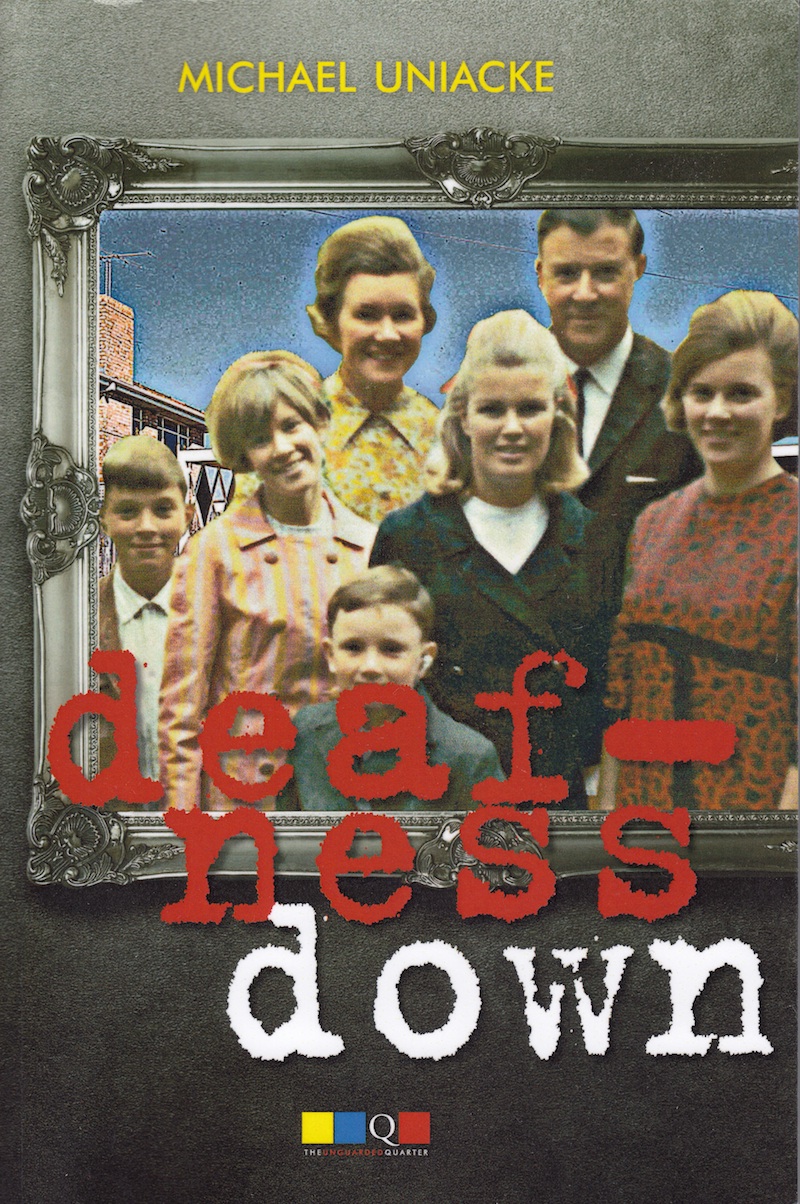

A few weeks ago, I helped a friend called Michael Uniacke to launch his book, Deafness Down. Here’s the short speech I gave.

Many years ago, I had a phone call from a total stranger called Michael Uniacke. He’d heard that I was a writer and writing teacher, and he wondered if I’d like to meet up with him and talk about the possibility of editing a book he was writing.

I must have asked him what kind of book: he must have told me it was an autobiography – and I’m pretty sure I told him that I was absolutely and utterly a fiction writer. Nevertheless, we did meet, at a cafe, and we sat talking for a long time. The upshot of the conversation was that, though I was a fiction writer, I agreed to have a go at being an editor as well. I am not an editor’s toenail, but it was with an unskilled but enthusiastic can-do spirit I entered into the project. And with great shame that I remember the many pages scribbled with red marks and the subtle-as-a brick comments. But Michael bore with it all very patiently; he wanted to learn; he wanted to communicate, and he wanted to tell his own unique story.

There – I’ve used the word – ‘story’. We humans love a story. Story is how our brains work, it’s how we understand our lives, it’s how we understand others and ourselves. Michael’s story centred his experience of deafness, and to me that subject was fascinating and utterly new. Not only did it do what good fiction and biography and memoir can do – which is to open a window into another person’s inner life – but it was genuinely educative. Like most people not personally touched by deafness, I’d never come across the concept of ‘deaf culture’. Michael talked to me about the 1880 Congress of Milan, where educators of deaf people made a decision that signing was to be more or less banned. I encouraged him in his interest and exploration, and he came back with the most extraordinary stand-alone piece of writing. It was so dramatic, so imaginative that I was astonished. Who would have thought that this kind of story-teller was sitting there inside?

My work on the project ceased – I had a baby. Now, that baby has just started University! – So this was all a long time ago. However, there’s nothing wrong with a long period of gestation for a work such as this. Autobiography is about life seen and understood backwards – how can it be anything else? And the long view brings a greater perspective.

Which brings me to the original title of the book. It was ‘The Dragonfly’. This last week, in the very hot weather, I spent many hours in my neighbour’s pool. I rescued quite a few drowning bees, and watched the dragonflies skimming the surface. As I understood it, back then, the dragonfly symbol related to deafness in this way – the dragonfly, with its 360 degree vision aligned to its hovering, skimming flight, is able to sensitively and almost invisibly extract from the air what it needs to survive. The metaphor is the superbly attuned senses; the toughness; the survival. I wondered what else the dragonfly might symbolise, so of course I Googled.

And found that to the Japanese, it represents power, agility and victory. To the Chinese, prosperity, harmony and good luck. That’s very nice, I thought. But it was the Native Americans, to me, who said it all. They believe that, because it can fly in all directions – that means up and down and backwards as well – looking though those amazing eyes , it can represent a being who sees the world through many perspectives. And seeing the world like that, is emotional maturity. And that is a very lovely and very appropriate meaning for Michael’s story.

So that is the story of my involvement, over 20 years ago, with that part of Michael’s writing career. His passion to communicate hasn’t abated.I’m happy and honoured that he’s asked me to help celebrate.

Deafness Down and its sequel, Deafness Gain, are available in print from online book retailers, at Stonemans Bookroom in Castlemaine and as an eBook from www.tuq.pub/book/deafness-gain/