It’s odd how sometimes everything connects.

In last Saturday’s Age was an article titled The Day the Dog Died… by Aisha Dow. The dog died in the living room, at the foot of the sofa, and it stayed there, decomposing, until ‘all that was left was a large, perfectly formed skeleton and a muddy brown stain.‘

Horrible, yes? But there was worse. The owner of the dog and living room was a 79 year old woman who’d been in hospital. When a social worker and an occupational therapist visited her home, in order to get it ready for her discharge, they found not only the dead dog, but floors covered with bags of rubbish, cigarette butts and piles of Wheels on Meals containers. Oh, and a cardboard box filled with toilet paper and faeces. As Dow writes, ‘…the workers had stumbled across a squalid household.’

She goes on to explain that ‘domestic squalor is not a distinct medical condition, but rather is described as a living environment that has become so unclean, messy and unhygienic that people of a similar culture would find cleaning and clearing essential’.

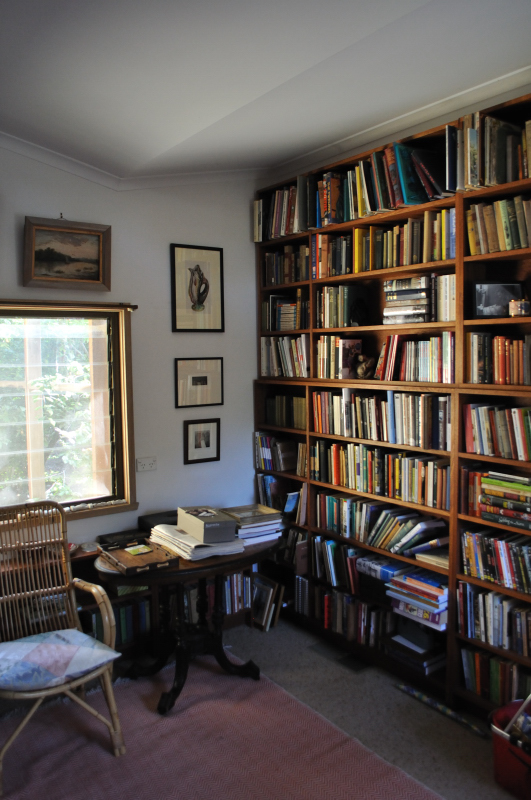

This article, combined with my current book, The Making of Home by Judith Flanders, led to much meditating on the notion of ‘home’. My family home, in its three different locations. The various homes I’ve made for myself, by myself and with others. Homes I’ve visited and stayed in, some of which were so ‘unclean, messy and unhygienic’ that it was only an over-developed sense of politeness that made me sip tea from the dirty cup and gingerly nibble the food I was offered. I remembered the house of a childhood friend which was so clean, so neat, so full of light and shiny surfaces and admirable storage solutions that I was homesick, even though our place was always a bit of a tip. This family had no art on the walls and no books. I noticed that more than anything. It felt weird. And the house of an acquaintance that was not especially dirty, but so messy that it looked as if a giant had come along and thrown all her stuff in the air. To find something – the phone, keys, a book, a plate – she shuffled the stuff around, thus covering and hiding other things. Also, weird. But both ‘home’.

This article, combined with my current book, The Making of Home by Judith Flanders, led to much meditating on the notion of ‘home’. My family home, in its three different locations. The various homes I’ve made for myself, by myself and with others. Homes I’ve visited and stayed in, some of which were so ‘unclean, messy and unhygienic’ that it was only an over-developed sense of politeness that made me sip tea from the dirty cup and gingerly nibble the food I was offered. I remembered the house of a childhood friend which was so clean, so neat, so full of light and shiny surfaces and admirable storage solutions that I was homesick, even though our place was always a bit of a tip. This family had no art on the walls and no books. I noticed that more than anything. It felt weird. And the house of an acquaintance that was not especially dirty, but so messy that it looked as if a giant had come along and thrown all her stuff in the air. To find something – the phone, keys, a book, a plate – she shuffled the stuff around, thus covering and hiding other things. Also, weird. But both ‘home’.

Flanders looks at the evolution of the house in Northern Europe, Britain and the USA from the 16th to the early 20th century and shows that what we think ‘home’ is and what it actually was are two very different things. In earlier times, furniture and what we now call ‘home-wares’ were so expensive that nobody had much. The household furnishings of a moderately prosperous family well into the late 17th century formed a very short inventory: a table, some benches and stools, a chair (that is, one chair and one only, for it was not uncommon for the father to eat sitting while everyone else stood), a cupboard, a modest batterie de cuisine and a few tubs, buckets, blankets, trunks and the like. These goods were valuable. They were mentioned in wills; they were handed down the generations. (As were clothes. Another story).

The house was as much a work-place as a living place. The household needed to produce much of what it took to keep everyone fed, clothed and sheltered, and some family members may have also earned money from trades such as weaving or knitting. There was no expectation of privacy. Beds – and only the well-off actually owned beds, the rest of us slept on straw – were in public rooms, for there weren’t separate rooms for separate occupations such as sleeping, cooking, working and relaxation as there are now – it was all in together. Warmth from fire or stove, and light from lamps or candles was concentrated in one area – another good reason for togetherness.

What changed these houses into ‘homes’ as we commonly think of them – as special and separate, almost sacred; retreats from the harsh outside world; places of ultimate comfort and intimacy where you can ‘be yourself’ – was, according to Flanders, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism.

The article and the book connected with my visit to the Op Shop which has – hooray – just re-opened after the Christmas break. The stuff! (We won’t even talk about the clothes.) It felt wrong, somehow. The piles and shelves of perfectly good, serviceable, not unattractive (and yes, let’s face it, some frankly hideous) crockery and cutlery and bedding and table-linen and assorted home-wares… For under $20 I could have taken home stuff in quantities that the ‘moderately prosperous family of the late 17th century’ would have found astonishing. They’d have thought I was super, super rich. This stuff has been donated, in most cases, because the folk who owned it have bought different or better stuff. I do it myself, of course. I buy stuff. We all do.

But I also use that brown Derby casserole that my parents brought back from England in 1952.

Home. I have often wondered what it would feel like to live in a house where nothing had a history. Where it was all new. As would happen to us if, for instance, we were in the path of a bush-fire. How would I feel ‘at home’ if my personal history was invisible?

Home. I have often wondered what it would feel like to live in a house where nothing had a history. Where it was all new. As would happen to us if, for instance, we were in the path of a bush-fire. How would I feel ‘at home’ if my personal history was invisible?