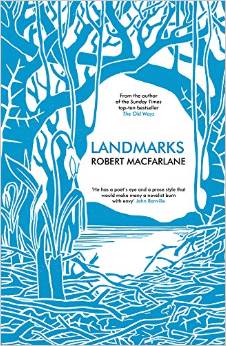

I have been reading the new Robert Macfarlane, Landmarks. An intense language experience. Something that I first realised many years ago, when I was first beginning to write as an adult, is that specific vocabularies, the real words for things, the precise and pointedly correct words for things and about things, add power and weight and beauty. Margaret Attwood’s Life on Earth was the book that showed me this. It’s probably more than thirty years since I read it, but think I remember the heroine worked in a museum. There were all sorts of sciency words. They were wonderful.

Landmarks is a book about observing, really looking and seeing. About finding the words and metaphors and similes that are right, tight, apt and precise for the humanly-observed, -walked, -worked, -sailed, -climbed, -loved world. Words for waves and rocks and cliffs and paths and mountainsides and stones and rain and hail and winds… A quob is a shaking bog in Herefordshire. Kynance is Cornish for gorge. And a gloup or glupe is an opening in the roof of a sea cave through which the pressure of incoming waves may force air to rush upwards, or water to jet and spout. That’s in the Hebrides, Orkney and Shetland.

I have often felt that I should should should learn the names of plants and birds that inhabit this place where I live and that I love so much. And at the same time I’ve resisted, because (1) I am lazy and it’s too much trouble and (2) I have thought that loving can be looking; it doesn’t need to be naming. But thinking about it, I realise that naming is loving and knowing. For instance, there’s a plant called Veronica perfoliata (I just looked this up!) but its common name is Digger’s Speedwell. Diggers are miners; so that plant was named by them during the goldrush. And I guess it was named before that, by the Dja Dja Wurrung people who were here first. What, I wonder?

I was weeding in the garden earlier. I know oxalis and cleavers and dandelion, but that’s about it. What were the two plants I was so ruthlessly removing? I felt with my hand and wrist and arm and back the difference between them. You grasp the grass (grass? which grass?), making sure you get all the blades in your fist, and pull. Sometimes you have to tug a bit, or rock the clump of grass, to get the roots to give. Then it comes up out of the ground in a hearty, satisfying way. You have to shake off the soil – again, heartily. When you’ve pulled a few, your tub is nice and full. It’s a fun thing to weed. The other one is not a robust experience at all. It’s more of a fine-motor thing. You have to pick the main stem, and pull gently or else the fine sticky filaments that are its roots just cling to the soil and most of it stays there. You can weed out the grass quickly, but this one needs patience for its fineness.

I was weeding in the garden earlier. I know oxalis and cleavers and dandelion, but that’s about it. What were the two plants I was so ruthlessly removing? I felt with my hand and wrist and arm and back the difference between them. You grasp the grass (grass? which grass?), making sure you get all the blades in your fist, and pull. Sometimes you have to tug a bit, or rock the clump of grass, to get the roots to give. Then it comes up out of the ground in a hearty, satisfying way. You have to shake off the soil – again, heartily. When you’ve pulled a few, your tub is nice and full. It’s a fun thing to weed. The other one is not a robust experience at all. It’s more of a fine-motor thing. You have to pick the main stem, and pull gently or else the fine sticky filaments that are its roots just cling to the soil and most of it stays there. You can weed out the grass quickly, but this one needs patience for its fineness.

Perhaps I will give them my own common names – Easy-Out Grass and Little Stickies, perhaps.