“Nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. Amen.”

“Nunc et in hora mortis nostrae. Amen.”

The daily recital of the Rosary was over. For half an hour the steady voice of the Prince had recalled the Sorrowful and the Glorious Mysteries; for half an hour other voices had interwoven a lilting hum from which, now and then, would chime some unlikely word; love, virginity, death; and during that hum the whole aspect of the rococo drawing-room seemed to change; even the parrots spreading iridescent wings over the silken walls appeared abashed; even the Magdalen between the two windows looked a penitent and not just a handsome blonde lost in some dubious daydream as she usually was.

I first read The Leopard in 1975 (a half century ago! a whole world away!) when it was a set text for HSC English Literature. From the very first paragraph (above), I was in love.

I first read The Leopard in 1975 (a half century ago! a whole world away!) when it was a set text for HSC English Literature. From the very first paragraph (above), I was in love.

With everything. With the Prince and his family, who we see first at prayer in their frescoed room surrounded by painted Roman gods and goddesses – ‘thunderous Jove and frowning Mars and languid Venus’ and a mob of minor deities. With Sicily, which is a protagonist in its own right; the heat, the langour, the lavish beauty and cruelty, the history of invasion and colonisation, the decay. And most of all with the writing; its rhythm, its parade of semi-colons (which my own editors have always wanted to remove), its complex, flowing, allusive and beautiful sentences and paragraphs that weave an instant time-travelling spell. I am there, in May 1860, at the Villa Salina near Palermo.

Fabrizio, Prince of Salina, is the ‘Leopard’ of the title, around whom the novel revolves.

…(the Prince) had risen to his feet; the sudden movement of his huge frame made the floor tremble, and a glint of pride flashed in his light-blue eyes at this fleeting confirmation of his lordship over both humans and their works.

…(the Prince) had risen to his feet; the sudden movement of his huge frame made the floor tremble, and a glint of pride flashed in his light-blue eyes at this fleeting confirmation of his lordship over both humans and their works.

He is a conundrum of a man. Half-German, half-Sicilian, tall, huge and fair among his slighter, dark-haired kin, see-sawing between sensuality and intellect. He can be irascible, sentimental, intellectual, cynical, philosophical, melancholic, inattentive to practical matters and also ruthlessly pragmatic. He rules his family like Zeus over Olympus – he loves them, they fear him – but with the end of the Bourbon regime, the influence of his class is about to wane. The novel follows the Prince as he negotiates, with melancholy realism, the new reality ushered in by the unification of Italy. His class, he knows, must fade into irrelevance as the middle class supplants them.

slighter, dark-haired kin, see-sawing between sensuality and intellect. He can be irascible, sentimental, intellectual, cynical, philosophical, melancholic, inattentive to practical matters and also ruthlessly pragmatic. He rules his family like Zeus over Olympus – he loves them, they fear him – but with the end of the Bourbon regime, the influence of his class is about to wane. The novel follows the Prince as he negotiates, with melancholy realism, the new reality ushered in by the unification of Italy. His class, he knows, must fade into irrelevance as the middle class supplants them.

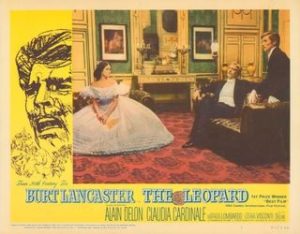

I only just found out that there’s a 6-part Netflix series out soon. I’ve seen the 1963 Visconti film a few times, including once with the ball scene restored to its full 50-minutes. American actor Burt Lancaster played the Prince, with Frenchman Alain Delon as his nephew Tancredi and Italian Claudia Cardinale his nouveau riche fiancee Angelica. It seemed perfectly cast. Can I bear to watch the new version?

I only just found out that there’s a 6-part Netflix series out soon. I’ve seen the 1963 Visconti film a few times, including once with the ball scene restored to its full 50-minutes. American actor Burt Lancaster played the Prince, with Frenchman Alain Delon as his nephew Tancredi and Italian Claudia Cardinale his nouveau riche fiancee Angelica. It seemed perfectly cast. Can I bear to watch the new version?

I can certainly re-read The Leopard and know my expectations will be met. After fifty years and a lot of other reading, it remains in my mind a near perfect novel. And I could say perfect, but won’t for fear of provoking those gods of di Lampedusa’s.

I’ve never seen the Visconti film (I don’t think) but I’m excited for the Netflix series — it looks pretty sumptuous. And time for a re-read before it comes out…