In museums, libraries and the landscape, a memory remains of a wilderness of unquiet graves, riddling marshes and storm-beaten cliffs. The stories to come and the commentaries that follow them were inspired by these memories, found in cultural artefacts whose words and images shed light on the idea of the wild in early medieval Britain. I sought to capture flashes of the cruel garnet eyes that wink from the treasures of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, and the beautiful, haunting atmosphere of the Old English elegies, Welsh englynion and the Irish immrama. These survivals – whether poetic, artistic, carved from whales’s bone or cast in solid gold – were forged by cultures with a world view very different to our own. My aim has been to evoke and contextualise an ancient imaginative landscape.

In museums, libraries and the landscape, a memory remains of a wilderness of unquiet graves, riddling marshes and storm-beaten cliffs. The stories to come and the commentaries that follow them were inspired by these memories, found in cultural artefacts whose words and images shed light on the idea of the wild in early medieval Britain. I sought to capture flashes of the cruel garnet eyes that wink from the treasures of the Sutton Hoo ship burial, and the beautiful, haunting atmosphere of the Old English elegies, Welsh englynion and the Irish immrama. These survivals – whether poetic, artistic, carved from whales’s bone or cast in solid gold – were forged by cultures with a world view very different to our own. My aim has been to evoke and contextualise an ancient imaginative landscape.

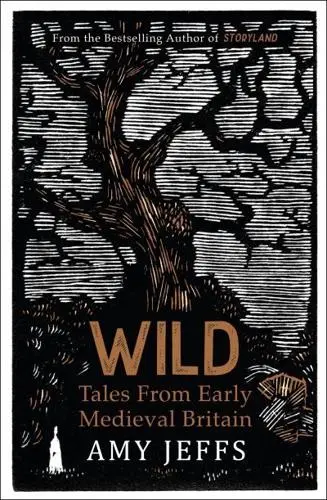

In Wild: Tales From Early Medieval Britain, Amy Jeffs leads the reader through stories dating from the turbulent period circa 600 to 1000, through a landscape which seems cold, inhospitable and threatening, among people with not just ‘very different’ but almost incomprehensible lives and beliefs. Invasions, migrations and power struggles convulsed early Britain – depending on where a person lived, it was the Celtic Britons, settlers from various Germanic tribes, clans from across the Irish sea warring with the Picts, and of course, the Vikings… And the weather was really, really bad. An ‘ice-encrusted, storm-swept, eel-infested, midnight-sun-illuminated wilderness’.

I was expecting to read, as well as commentary, accessible translations or re-tellings of ancient texts. Instead, Jeffs has created a series of seven tales, combining elements of these texts. Even more unexpected was how visceral, immediate, vivid they are. The first, The Lament of Hos, begins:

Cold it is, cold and so close that I can feel my neighbours against me, their beards and bones rotting like stacks of winter branches. I hear the voices of elves, goblins and old gods that haunt these unhallowed halls. They whisper that I am friendless: that my old companions are dead, that my love has left me forever, that I must hope without hope until I am no more than an ache in the air.

The narrator is a young wife who has been betrayed by her lover, captured by her lord’s kinsmen, executed and thrown into the ‘unhallowed halls’ of a cave or an ancient burial mound where she lives on as a ghost or spirit. It makes me think of those terrifying scenes among the un-dead in The Lord of the Rings. Probably some of the genuine sense of claustrophobia comes from Jeffs’ research. She’s not just rootling around in libraries among Old English tomes; she goes on a caving expedition herself. Only fifteen minutes, crawling around at night under the Mendip Hills in south-west England, but as someone who’s pretty much cave-, cavern- and tunnel-averse, it was a bit too well observed.

What a weird, unsettling and unusual book this is. I mean that as a recommendation! And original wood engravings by the author are an added bonus.