As I read the biographies, I began to see that just as patriarchy allowed Orwell to benefit from his wife’s invisible work, it then allowed biographers to give the impression that he did it all, alone. The biographers are choosing the facts of this story in a world that has already sifted them in his favour. The narrative techniques of patriarchy and biography combine seamlessly so as to leave the women who taught and nurtured Orwell, influenced and helped him, like offcuts on the editing floor, buttresses to be removed once the edifice is up.

And so I write, as Orwell put it, because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention. Or, as it happens, a person.

I was so shattered by this book that I have had to have a week of gardening books and a dose of Elizabeth Goudge to recover. And that’s not because George Orwell is one of my heroes and I was having an attack of the vapours over his clay feet. I probably should be ashamed to admit that I’ve never read anything except the essay Why I Write. Yes, that’s correct, I have not read 1984 or Animal Farm or Homage to Catalonia. I do know about these books, however, and understand how important a writer and thinker Orwell is. I know that he reported on his lived experience amongst the poor in London and Paris, fought in the Spanish Civil War, and in his writing sought to expose the true horrors of communism. He championed honesty and integrity in words and actions; he was on the side of the underdog. And I knew he died young, at only 46.

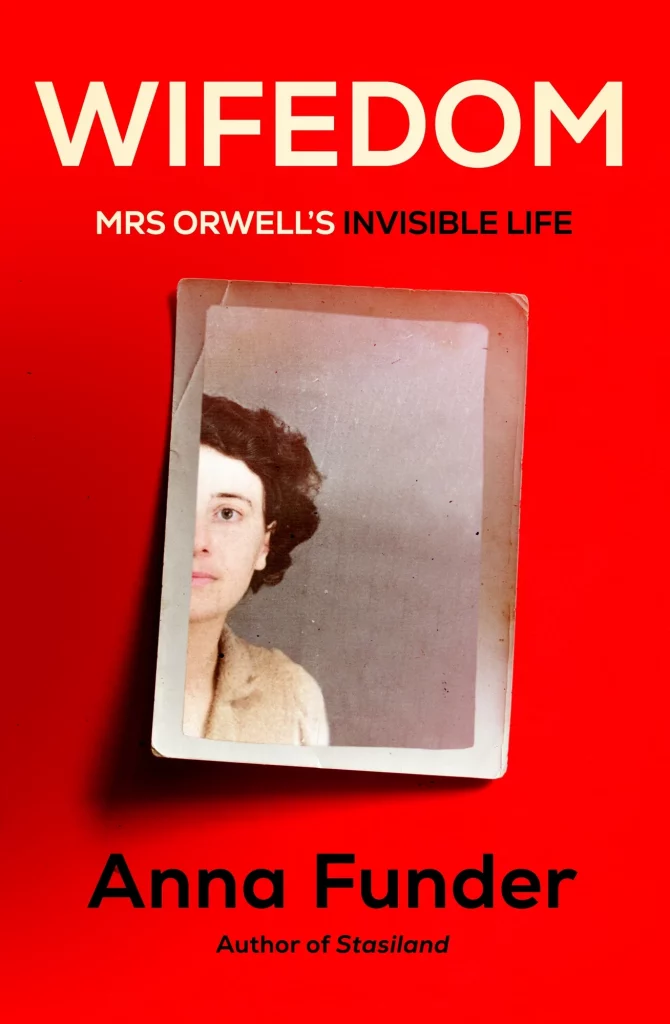

But I didn’t know anything about Eileen O’Shaughnessy, Orwell’s wife.

Funder’s painstaking research, reading between the lines of Orwell’s well-documented life and a cache of letters discovered in 2005, reveals her as the wife who believed in him, encouraged him, discussed and read his work, edited and commented on it and typed it. She is the woman who also went to Spain to fight the Fascists. She was the woman who worked the double shift of paid employment and housework while they lived in London and then moved with him to a primitive country cottage without sanitation, electricity or running water, where she looked after the animals and ran the little shop and did the housework and shopping and cooking and everything else. One episode that has lodged in my mind is Eileen outside, wearing fishing waders, knee deep in shit because of the overflowing toilet and Orwell opening the window and calling out that it must be time for tea. Which does not mean she should have a rest, and he would make her a cuppa. No, it meant she should make him his tea.

She took care of the shit.

While she did that, Orwell wrote and published, though for most of their marriage not much actual money came in. Funder is good at making this life sound like a slog and a struggle for both of them. Eileen cared deeply about her husband’s work, but Funder can’t find that in return he was appreciative of her labour and sacrifice. He didn’t cherish and care for her. Instead, he was not only consumed by his writing but also consistently unfaithful, sometimes even juggling a couple of lovers at a time and constantly pursuing young women. Back in the day these opportunistic advances were described as ‘pouncing’; today we’d probably call them out as sexual assault or attempted rape. I suppose this could be, if not excused, then at least explained as ‘other times, other mores’ except. Except – shouldn’t someone like Orwell, a man who exposed hypocrisy and injustice, be better than this? Shouldn’t he, of all people, not have ‘pounced’, or slept with teenaged Moroccan prostitutes or his wife’s friends?

Eileen had struggled for years with debilitatingly heavy bleeding, abdominal pain and anemia. Eventually, a mass of uterine tumours was revealed and in 1945 something had to be done. Orwell didn’t stay to take care of her; at the time an operation became imperative he was in France, writing and researching. Oh, and by the way, largely by his desire, they had just adopted a baby. The letters she wrote to him just before she died, after going by herself on buses and trains from London to a hospital in Newcastle-on-Tyne, are heartbreaking.

In London they said I couldn’t have any kind of operation without a preparatory month of blood transfusions, etc. Here I’m going in next Wednesday to be done next Thursday. Apart from its other advantages this will save money, a lot of money. And that’s as well. By the way, if you could write a letter, that would be nice.

And

…what worries me is that I really don’t think I’m worth the money.

This operation on the cheap killed her. The inquest found the surgeon and the hospital blameless, though it was noted that she was severely anemic.

Funder, trying to imagine what Orwell might have gone through reading these last letters, writes:

If you don’t care for someone, will they care less for themselves? He remembers his shock when the vicar left the word ‘obey’ out of her marriage vows. ‘I couldn’t very well have asked your permission not to ‘obey’!’ she’d laughed.

What had he done?

There are 67 reserves after me for this book at the Goldfields library and I’m betting that most readers will finish it feeling pretty shattered too. And Orwell’s feet most definitely are.

This is such a big, important, emotional book. I even persuaded my husband, who is not a reader, but who is a fan of Orwell (largely because of Spain), to listen to the audiobook; he kept returning from walks saying, oh my God, George Orwell was such a prick. It keeps resonating with me and I’m finding echoes in all kinds of things I’ve read since. We can only imagine what Eileen might have achieved if she’d had the kind of support that she gave so unstintingly to her husband. Animal Farm could be a clue.