…this theme – this transcendent theme – of fulfillment and non-fulfillment; and those who bind themselves to limitations…

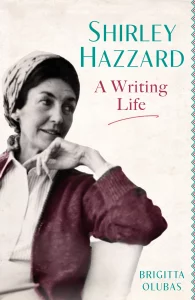

Shirley Hazzard, with a small output, has a huge reputation. And this biography, by Australian academic Brigitta Olubas, is also huge – 780 grams, 467 pages plus another hundred or so comprising photographs, notes, acknowledgements and index.

That’s a lot of Shirley. For this reader, perhaps a bit too much.

Everyone seems to agree that Hazzard was a great stylist. The Great Fire was certainly full of sentences and phrases and paragraphs that are literary, precise and often beautiful or striking. Or depending on your point of view, mannered or even intrusive, with more than a touch of Henry James* (though she always denied his influence), with that way of interrogating every little detail until you want to scream. I didn’t enjoy it much, but I do plan to re-read The Transit of Venus.

I remember loving that book when I was in my early twenties. It’s spoken of as her best novel, and I think I’ll be able to appreciate it more than The Great Fire.

Maybe. After reading this biography, I’m hesitant about spending any more time with her. It’s going to be quite a task to separate the writing from the woman.

Hazzard was born in 1931 into a middle-class Sydney family. Her father Reg worked for the company that built the Sydney Harbour Bridge, and later for the Australian government as a diplomat exploring international trade possibilities. He was also an alcoholic, with a long-term mistress who followed the family to their overseas postings. Her mother Kit, an elegant and beautiful woman, was probably bipolar, and a difficult, demanding and turbulent presence in her life. Her older sister, Valerie, contracted TB when Shirley was a teenager. They were not close. It doesn’t sound like a happy childhood.

As a girl and young woman, Shirley must have been intense company, constantly reading, thinking, noticing, describing, analysing…and writing, turning her life into literature. She was mad for poetry, learning Italian so that she could read her Italian poets not in translation and memorising whole poems which she could (and did) recite at the drop of a hat. Perhaps because of all that poetry, she was also mad for love. All-consuming, passionate, romantic capital-L Love.

Which she found when her father was posted to Hong Kong in 1947. She was 16. The man’s name was Alexis (Alec) Vedeniapine, a white Russian, an officer in the British army in his early thirties. He was charming, handsome, an intellectual as well as a man of action – and importantly, a lover of poetry. Forming the model for Aldred Leith, the hero of The Great Fire, he was “her first great love”. It was an experience she never forgot, and in many ways she carried the torch for that love her entire life. Though in 1947 they were separated (by her father’s further postings and medical treatment for Valerie), she considered herself engaged to Alec, exchanging letters when he returned to England to become a farmer – but not meeting. Olubas tells the story sympathetically but his 1950 letter asking her to break their engagement is actually quite funny. He painted a picture of himself and his farming life that is so bleak, so unappealing.

I feel and have felt for a long time that I have made a mess of things in thinking I could shape this life into something that I could ask you to share with me…I get up at half past four and work till dark. I never go out for pleasure and am too tired to live and think as a human being… There is nothing and nobody – it’s just that the life I had visualised is not coming out as planned and I see no light in the distance…

Oh God, he must have prayed, get me out of this, please! Did he feel hunted? How exhausting to be with a 19-year-old who was incapable of sharing his working life and practical interests, but who must always live at the “extremities of romance”, as Olubas describes it. Though Hazzard kept in touch with Alec for the rest of his life, she considered him a failure. He hadn’t met her high hopes for him (or expectations), and the things that meant so much to him – his marriage, his children, his farm – were negligible to her. She wrote, ‘He renounced his larger life.’ He had bound himself to limitations.

When her father was posted to America, Hazzard began working in secretarial roles for the UN in New York and indulged in a string of relationships with married or otherwise unavailable older men. She even went on family holidays with one lover, his wife and children. A trip to Naples to recover from one of her failed affairs changed her life; she fell under its spell, and almost until she died, she divided her time between Italy and New York. Her writing began to be published, the literary world of New York opened to her and in 1963, marriage to the much older, distinguished (and wealthy) writer and art lover Francis Steegmuller completed the picture. It was then she began to live her ideal life. She and Steegmuller went to the opera, collected art, socialised in artistic, cultured, intellectual circles, had an apartment on Capri, kept a gold Rolls-Royce – and wrote until old age and dementia took them both.

Her bibliography is sparse; four novels, three short story collections and a handful of non-fiction works, among them a couple of highly critical accounts of the UN, a memoir of her friendship with Graham Greene. Both The Transit of Venus and The Great Fire were highly acclaimed and awarded, but there was a 23 year wait between them for eager readers.

Olubas has written an admiring and almost fawning biography. I was left with the impression of a woman who was fastidious, refined, cultured, elegant, cultivated, beautiful, sophisticated, intelligent, brave (she took on the UN in her exposure of Kurt Waldheim’s Nazi past) and ambitious – but decidedly unappealing. Dominating, demanding, sensitive to coldness or criticism but often unable to understand other people’s needs and differences – or even to listen! – and almost emotionally stunted.

Hm, I think that might be too much Shirley Hazzard for me too. I know I’ve read The Great Fire but I can’t remember anything about it. Should I try Transit of Venus? I must admit it doesn’t sound hugely appealing!

I’ll keep you posted when I’ve read Transit of Venus.