The natural world is not, to me, a fabric of stuff that gleams with revelation of a singular creator god. Those moments in nature that provoke in me a sense of the divine are those in which my attention is unaccountably snagged on something small and transitory…things whose fugitive instances give me an overwhelming sense of how unlikely it is that in the days of my brief life I should be in the right place at the right time and possess sufficient quality of attention to see them at all…

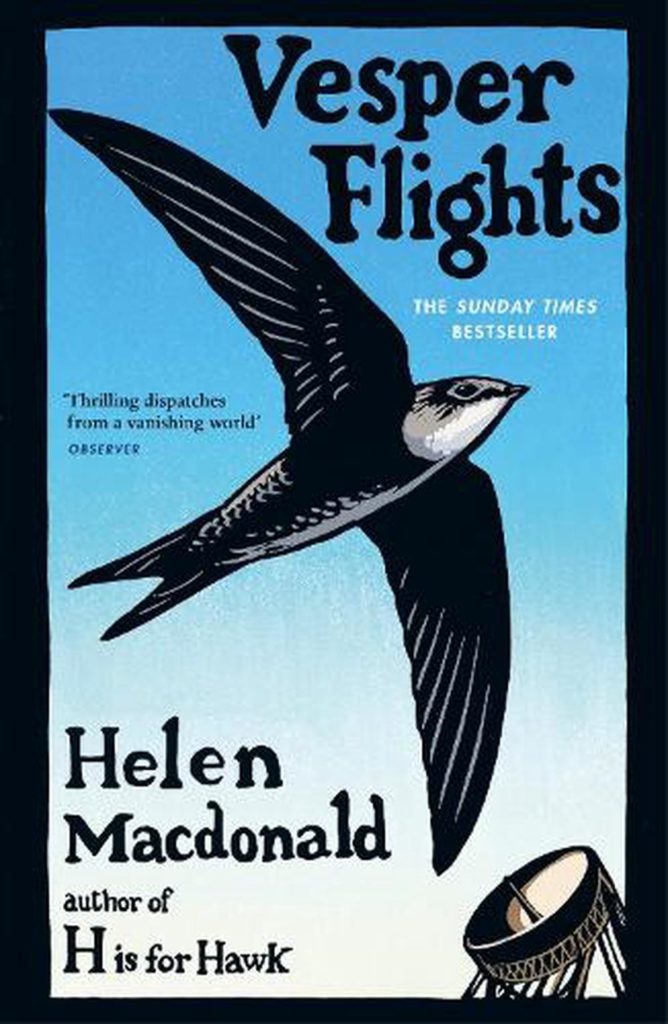

I have just finished Vesper Flights, and as with the best writing, how I see the world has changed, just a little. Helen McDonald writes with such beautiful clarity, and it feels as if she’s made sense of and put into words some of my own half-realised thoughts and feelings about my encounters with the natural world. Even though she is a British writer and so the creatures she describes are not ours, it seems the intensity and fascination of our human encounters with nature are the same the world over. Though obviously I would rather encounter a kangaroo than a grizzly bear…

I suppose you could say that birds are McDonald’s major subject (though here she does touch on pigs, deer, hares, squirrels and university students) – but that’s putting her into too small a box. Spirituality; grief and loss; science and research and the climate emergency; philosophy, history and literature – all these and more are interwoven with her own complex personal history in this series of essays. Above all, she illuminates what she calls ‘the numinous ordinary’, those moments that ‘open up a giddying glimpse into the inhuman systems of the world that operate on scales too small and too large and too complex for us to apprehend’.

Part of the numinousness in these encounters with nature is how unpredictable they are. There is no point in searching for them. In my experience if you go out hoping for revelation you will merely get rained upon.

And oddly enough, the day after I finished Vesper Flights, we had a bird encounter of our own. I don’t know that I would call it numinous, but it was intense. A bronzewing flew straight at our window. It’s happened before. The last time, the bird died and the replacement glass cost nearly $700. This time, there was a mighty bang, but no smash. When we ran into the room, we saw a smear of oily brown on the glass and a motionless bird lying on the path below. We watched anxiously. Was it dead? Was it terribly injured? Did it have a broken wing, and would one of us have to go down and wring its neck so the neighbourhood cats didn’t get at it? Little by little it began to move. Eventually it stood up. It was just stunned. I felt like cheering.

We tried to imagine what the bird must be thinking, or feeling. Do bronzewings think? Why do they keep doing this? Why can’t they see it’s a living room, not a flight path? What does it think happened to it? Will it remember, and stay away?

But not being inside a bird brain, we can never know.

The title, Vesper Flights, refers to swifts:

On warm summer evenings swifts that aren’t sitting on eggs or tending their chicks fly low and fast, screaming in speeding packs around rooftops and spires. Later, they gather higher in the sky, their calls now so attenuated by air and distance that to the ear they corrode into something that seems less than sound, to suspicions of dust and glass. And then, all at once, as if summoned by a call or a bell, they rise higher and higher until they disappear from view. These ascents are called vespers flights, or vesper flights, after the Latin vesper for evening. Vespers are evening devotional prayers, the last and most solemn of the day, and I have always thought ‘vesper flights’ the most beautiful phrase, an ever-falling blue.

Helen McDonald writes so beautifully, reading her is like a prayer or an act of worship.

Yes. Perfectly expressed, Kate.