I promised myself to read more new books this year (new to me, I mean), and so I have been trawling through the library catalogue and earmarking any titles that take my fancy. I have 21 books on reserve at present! My fancies seem to coincide with lots of other borrowers, so that there’ll be a week or two with no books and then three or four come in all at once. Feast or famine.

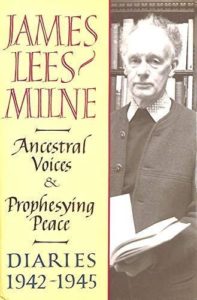

It was famine last week. Since we were heading off to the Grampians/Gariwerd for a holiday, I needed something riveting to read in case it rained all the time. So I took with me a couple of James Lees-Milne’s wartime diaries, Ancestral Voices (1942-3) and Prophesying Peace. (1944-5). James Lees-Milne? Who? He’s sometimes called ‘the man who saved England’. But we’re talking architecture, not military strategy – he was employed from 1942 to 1947 to inspect and assess historic buildings offered to the National Trust.

It was famine last week. Since we were heading off to the Grampians/Gariwerd for a holiday, I needed something riveting to read in case it rained all the time. So I took with me a couple of James Lees-Milne’s wartime diaries, Ancestral Voices (1942-3) and Prophesying Peace. (1944-5). James Lees-Milne? Who? He’s sometimes called ‘the man who saved England’. But we’re talking architecture, not military strategy – he was employed from 1942 to 1947 to inspect and assess historic buildings offered to the National Trust.

At that time, the National Trust was mainly concerned with preserving notable landscapes; it owned 75,000 acres but had less than ten historic houses open to the public. These houses weren’t seen as a vital part of the country’s heritage; consequently if the owners didn’t have the funds for upkeep, they were demolished or left to decay. Requisitioned for wartime use, some of them were being severely damaged. Into the breach leaped a small, amateurish but committed band of National Trust employees. Lees-Milne had an insatiable passion for architecture and the old and often dilapidated great country houses of England. It sounds as if, with his love and enthusiasm and tact, he often charmed the owners (who were often old and dilapidated, too) into passing their precious family seats into the care of the Trust. But not always.

I had a horrible day with Colonel Pemberton at Pyrland Hall near Taunton. He is a fiendish old imbecile with a grotesque white moustache. When I first saw him he was pirouetting on his toes in the road. He has an inordinate opinion of himself and his own judgement… Having hated me like poison he was nevertheless furious when I left at 4pm. I conclude he has to have a victim on whom to vent his spleen.

The last time I read these diaries must have been pre-Internet. With a a few clicks now I can bring up an image and see for myself what Lees-Milne is talking about. This is Kelmscott, the home of Arts and Crafts artist and designer William Morris.

The last time I read these diaries must have been pre-Internet. With a a few clicks now I can bring up an image and see for myself what Lees-Milne is talking about. This is Kelmscott, the home of Arts and Crafts artist and designer William Morris.

The old, grey stone, pointed gables are first seen through the trees. The house is surrounded by a dovecote and farm buildings which are still used by a farmer. The romantic group must look exactly as it did when William Morris found it lying in the low water meadows, quiet and dreaming… The garden is divine, crammed with flowers wild and tangled, an enchanted orchard garden for there are fruit trees and a mulberry planted by Morris. All the flowers are as Pre-Raphaelite as the house, being rosemary, orange-smelling lilies,, lemon-smelling verbena. The windows outside have small pediments over them. Inside are Charles II chimneypieces, countrified by rude Renaissance scrolls at the base of the jambs.

Pediments? Jambs? Rude scrolls? Now it’s easy to find out what they are.

The diaries aren’t just about driving in unreliable cars to visit eccentric aristocrats in remote mansions. These first volumes take in the worst days of the Blitz and he often found himself cleaning up bomb damage, watching for fires or sitting all night in a shelter. In one entry, he helped a crowd of people to make a chain of hands in order to rescue rare books from a bombed-out library. And he always found time to socialise. He was friends with all sorts of artists, writers, historians and cultured celebrities – with literati like Nancy Mitford, Vita Sackville-West and Ivy Compton-Burnett – and a crew of glittering but now-forgotten socialites such as Emerald Cunard and Daisy Fellowes. They all seemed to manage to wine and dine and spout witticisms amongst the death and destruction.

These diaries wouldn’t be to everyone’s taste – he’s a snob, and his comments about ‘the lower orders’ are a bit hard to take – especially since I would have been one of them! But for all that, Lees-Milne’s mixture of people and places, historical and architectural knowledge, description, philosophy, religion, anecdotes, gossip, opinions, complaints, doubts and fears and failings is addictive reading. He was candid about his personal life and curious about other people’s. Often malicious or waspish, but at times surprisingly compassionate. In one entry, he’s conscience-stricken that he unintentionally “cut” a working-class fire-watching colleague, and berates himself for hurting the man’s feelings. All in all, a good companion to take on a holiday.

Ooh, this sounds wonderful! Right up my alley (and I shamefully confess I quite enjoy a bit of waspish snobbery). I will keep my eye out.